Interview with Dr Alexander Plekhanov, Director for Transition Impact and Global Economics and Richard Jones, AIIB-EBRD Business Development Director of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Alexander Plekhanov and Richard Jones gave a presentation on "EBRD Transition Report 2018-19 – Work in Transition" at CityU in March 2019. City Business Magazine took the opportunity to extend the conversation.

| EBRD |

|---|

|

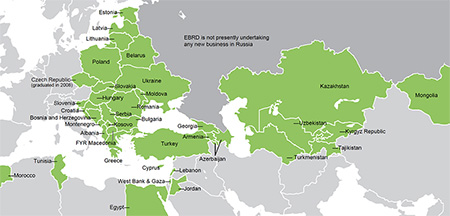

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development is a multilateral developmental investment bank founded in 1991. The EBRD uses investment as a tool to build market economies. Initially focused on the countries of the former eastern bloc, it has expanded to support development in more than 30 countries from Eastern Europe to Central Asia. Headquartered in London, the EBRD is owned by two European Union institutions as well as 68 countries including China and India. Despite its public sector shareholders, it invests in private enterprises, together with commercial partners.

|

Could you tell us a little bit about the early history of the EBRD?

Richard: The EBRD was set up relatively quickly to meet the challenge of an extraordinary moment in Europe's history, the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. The bank was actually established just before the dissolution of the Soviet Union which became a founding shareholder. That explains why the legacy states of the Soviet Union, including those in Central Asian countries, subsequently became shareholders and recipient countries. The EBRD was a European-led initiative, a Franco-German-British arrangement. Although it was a French idea, and the first President was French, the headquarters was placed in London, and it had a City of London culture grounded in merchant banking and was an investment banking platform from the beginning.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, what was the bank's transition philosophy?

Alex: The time when the bank was established coincided with the peak of the Washington Consensus. There was a belief that a lot could be done by maximising the involvement of the private sector and minimising the involvement of the state. The early days were very much about supporting private ownership and privatisation. The other elements that people recognised as important had to do with building institutions, such as the frameworks of the legal system behind the markets, and transfer of skills. In the early days of transition, there was a very strong decompression of wages and rising inequality, and market-relevant skills were in very short supply. People who had the skills commanded a high wage premium.

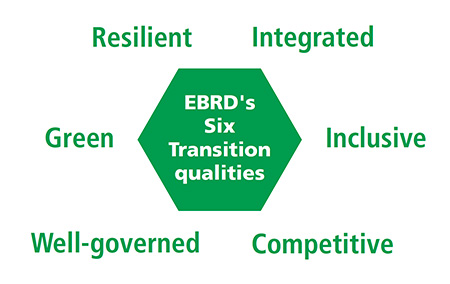

So that was the early vision. Over the years the understanding evolved that private ownership on its own can achieve only so much. A well-functioning state, backed up by functional institutions is also needed, and so the concept of transition grew organically. With greater realisation of green aspects and the pollution that can come 33with rapid development, people came to see the Soviet legacy as one of very dirty industrial production. Previous central planning models didn't have any environmental shadow pricing built into them. Over the years people also felt that if reforms came with a lot of hardship and rising inequality, there could be a strong backlash which in the long-term may be very counterproductive for economic development and market building. So, the inclusion angle became a lot stronger.

I think that the East European economies at large benefited a lot from foreign direct investment and skills transfer but some economies got integrated much more strongly into the global system than others. So, an emphasis on integration came into the EBRD thinking. Then with the Asian crisis of 1997, the ensuing 1998 crisis in Russia and the neighbourhood, and also later when the 2008-9 crisis hit, people realised that the resilience of economies was also key.

In 2016 we formally revised our vision of transition to incorporate all these elements. So, in addition to a competitive interpretation which has a lot to do with building well-functioning private-led markets, there is now emphasis on governance, on green, on inclusion, on economic integration, and on resilience. These are the six pillars that the bank works with at the moment.

EBRD's investment footprint

Source: EBRD

How important is the idea of economic integration in the EBRD's work?

Alex: In general, integration is built into implementation of our mandate these days. We have looked at the experience of union building around the world and I think in general, making trade across borders easier, making movement of skills and capital easier, are good things. If it comes at the expense of building harder borders around a union that may be problematic so that's one balance to strike.

A lot of economic integration has come about with the export of institutions. In NAFTA the US is the core and they try to organise production and the rules of the game in Mexico a little bit along US lines. The European Union does the same, with accession countries having to sign up to the "Acquis Communautaire", the accumulated body of EU law and obligations from 1958 to the present day. The EU accession process is a lot about building institutions, legal frameworks, ways of doing business that are similar to the core EU. Again, if we look at ASEAN in Southeast Asia this is anchored by Singapore and Malaysia. Over time there is an institutional convergence which is a very important element of institution building for developing economies.

In Central Asia however there is a real challenge. The supranational institution here is the Eurasian Economic Union, formed of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia. These countries have a fairly low level of economic and political institutions to start with. There is no core country with developed economic and political institutions that could be exporting to build the union-wide institutions, and that is what we highlighted in the Transition Report some years back.

When the EBRD assesses new projects, how important is the environmental aspect?

Richard: I think the EBRD was the first multilateral investment bank to have an environmental feature in its founding articles. We have always emphasised environmental compliance, risk avoidance and mitigation in projects that we finance. Increasingly however, it's also about environmental finance. This is very much focused on energy efficiency and helping firms and banks unlock the commercial benefits of reducing energy waste. This is also about policy dialogue with authorities to ensure that tariffs are set at a properly cost-effective level so that commercial incentives are in place for reducing energy waste. We have had a very strong programme for the past 15 years or more on energy efficiency finance across different sectors.

But more recently we've looked at resource efficiency and especially the use of water as water stresses in the Eurasian region are increasing, and also green power generation. We have a new focus, called the Green Economy Transition, and we are very focused on working with governments on the regulatory frameworks that permit investments in green energy and which we're financing on an increasing scale. This is an area where China of course is also very active industrially.

EBRD's Six Transition qualities

How did China's membership of the EBRD come about in 2016?

Richard: I think there have been discussions for many years in terms of the transition concept to market economy. I think that was interesting to Chinese policymakers. Another thing is that China is taking a greater role in the international financial architecture and organisations. I believe the EBRD was the last major multilateral development bank that China joined. And I think from the bank's side there was a recognition that China was a very important player in the regions where the EBRD was operating, and therefore it made good sense.

There is a significant overlap between areas where the EBRD and BRI are working.

Richard: Well yes, although BRI is quite hard to understand and define. If you look at Chinese outbound investment, then there are certainly areas where investments may align with our objectives, and in those cases, we are interested to talk to those investors and see if we can work together.

How can the EBRD and BRI projects align?

Richard: To take the China-Belarus Industrial Park project, there are several aspects. Firstly, we need to be financing projects that meet our standards so that's for example about environmental and social compliance standards. It's also about doing very careful financial due diligence to assess the risks, and about having a level playing field so that you are not benefiting firms from one block at the expense of another. For commercial reasons, the production in this industrial park will have to meet standards that are going to be compatible with export markets, principally the EU.

China has a lot of experience building industrial parks at home. How far can these projects be replicated in BRI projects?

Alex: Some industrial parks are immensely successful and some are ultimately rather problematic, such as in Saudi Arabia. I think they are very good examples of industrial parks that struggle to take off just because it's hard to find the skills and materials to populate them with production. For any project that is built it's really the analysis of that particular project, where it fits into the economy, what it links to which is key.

Great Stone China-Belarus industrial park

In our bank, Chinese contractors have always been free to bid for contracts that are competitively procured and I think they are successful about 25% of the time. This means there is serious expertise in China that is very competitive by international standards. Where Chinese companies have a particularly competitive expertise in an area, they are always welcome in a competitive tendering process.

How optimistic are you that BRI projects are environmentally beneficial?

Richard: If you look at the leader statements around the BRI, then green is very strongly emphasised but you have to look at the individual projects and that reveals the direction of the BRI. Although the BRI is looking at ways to green and climate proof infrastructure investments and although it's looking to finance green power, there are also examples of projects in coal-fired power generation which look as if they are going in the other direction. I guess the jury is out.

How do you envisage the EBRD's working relationship with China evolving over the next decade?

Richard: Well institutionally China is a very small shareholder, something like 0.1%, so I think the centre of gravity and governance of the bank is always going to be the EU and the European perspective. The relationship with China is more about Chinese businesses and Chinese banks in the countries where the EBRD is working. We'll want to continue to develop our business relations with those companies and banks where it makes sense from the perspective of our mandate and also to keep an eye on the risks of being a partner for our countries of operations.

How to create BRI projects which are more sustainable?

Richard: Well I don't think the problem is with Chinese financial institutions per se. China has excellent banks and industrial players who can do these projects very well in many cases. But I think you do have problems if you have first of all packages of investment that are agreed in a fairly closed system and in an opaque way. If it is a political agreement where the financier and the contractor come with the project design all in one package that isn’t clear to outsiders, then you're ruling out the expertise of the international community –including the Chinese international community. If you don't ensure that the standards are set from the outset, the economic due diligence, the environmental and social assessments, and the way that the project is going to be governed, that's a recipe for trouble.

Alex: I think also we have to look at infrastructure projects and their failures and successes in a broad context. Take Greece, which is by far the smallest economy to host the modern Olympics. I think it's about five times smaller in terms of GDP than Spain or Korea, the next smallest economies. So, Olympic infrastructure for Greece relative to the economy was very expensive and the way it was used after the Olympics has not been very smart in terms of converting this infrastructure into legacy. The Olympics made a very sizable contribution to Greece's financial problems, that became apparent after the 2008-9 financial crisis. These problems of making infrastructure smart and making it work for the long-term have existed since the beginning of time. I think the key is really for the recipient countries to be very smart about the kind of infrastructure they build, where, and how they use it for the long-term.

Dr Alexander Plekhanov

Director for Transition Impact and Global Economics

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

Richard Jones

AIIB-EBRD Business Development Director

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development