We all have an intuitive sense that ownership and control should be strongly related to economic incentives alignment - which is why we can't insure another person's property, as we would not suffer the loss of property, but we would gain from insurance payout.

Because publicly listed corporations are financed by external equity, but markets can't direct all resources of the firm, some decisions need to be delegated, meaning a separation between ownership (shareholders who have rights to cash flows) and control (e.g. CEO, board of directors, emplovees who can direct firm resources). Most academics come at this problem in a corporate context from the US perspective where ownership is typically dispersed among shareholders, and the board of directors (elected by shareholders) make decisions.

Our starting point

The US perspective fails to account for the global context where business groups - multiple publicly listed companies having the same ultimate owner - are a key part of the financial landscape. Outside the US, firms can be embedded in complex networks of ownership structures. This means that when you purchase a share of equity in a listed firm, the ultimate owner (controlling shareholder of that firm) may control the firm through another listed company. When a business group controls multiple firms, it has the flexibility to collect assets from each affiliated firm to build up the group's reserves and to reallocate them to those firms when needed. There is a long literature studying expropriation - where an owner tunnels assets out of a firm or a business group. However, we add a new perspective, given a network structure of interlocking ownership, some firms will be more important than others with respect to controlling business group assets.

Outline of theory

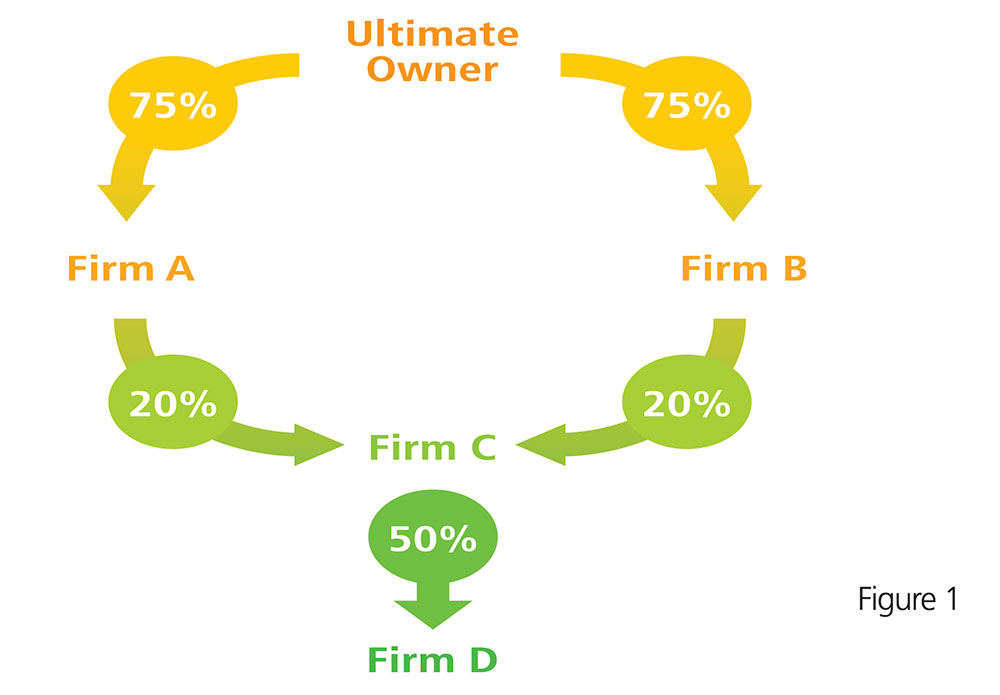

Consider Figure 1 to fix ideas. Let's assume that with dispersed ownership a blockholder with 20% ownership can control a firm and that each firm has an equal value.

If the ultimate owner loses control of firm A. he will still have a chain of ownership through firm B to control firms

C, and D. Likewise if the ultimate owner loses firm B he can still use firm A to control firms C and D. However, losing control over firm C would result in the loss of control of both firms C and D. In this case, we would call firm C a "central" firm, and the other firms are relatively

"peripheral" firms. This logic leads to the hypothesis that business group ultimate owners will protect their ownership over firms like firm C. In reality, the identification of ultimate owners and the calculation of centrality is computationally and economically challenging, and only recent advances in computational power made it feasible at a large scale. In our study, centrality is a continuous variable that captures the percentage of business group assets the ultimate owner would lose if they lost control of a given firm.

Business group ultimate owners protect their firms

The first thing we do is check whether business group ultimate owners indeed protect their most central firms.

We calculate unexpected industry shocks by taking the unforecasted shock from a prediction of industry sales, and then we analyse the sensitivity of central firms valuation (measured by market to book ratios) to these shocks. We find that a one standard deviation increase in centrality could offset approximately 12% of the negative impact of a negative shock. This observation is consistent with the notion that central firms are highly protected by business groups ultimate owners. We also construct a test using unexpected commodity price shocks. We find central firms' returns are much less sensitive to unexpected negative industry shocks. A one standard deviation increase in centrality could offset approximately 32% of the negative impact of this shock. These results suggest that central firms are indeed protected from shocks in the way we would expect.

Protected central firms have different stock return characteristics

Given the incentives for ultimate owners to protect central firms, and the empirical evidence in favour of this protection. It seems that centrality should be related to stock returns, in the sense that investors who realise these firms are less sensitive to shocks should also realise these firms are less risky, and thus command a lower risk premium (lower expected return). We can think of these firms like insurance; when bad things happen we know the ultimate owner will protect the firm, so we pay a premium for the firm (higher price) which means a lower expected return. We assess the evidence in multiple ways - we show that cross sectionally higher centrality means lower returns on average. A one-standard-deviation increase in centrality equates to a 14 basis points lower out-of-sample monthly return after controlling for common return predictors. We also build portfolios and find that higher centrality is related to lower returns on average. For example, we find across all firms high centrality portfolios have a 67 basis point lower monthly return (controlling for known predictors of portfolio returns) than high centrality portfolios. We also find that taking only the highest centrality firm from each business group, we high centrality firms have a 36bp lower return than low centrality firms, which indicates the effect holds even when we focus on differences between the most central firms across different business groups.

Is centrality distinct from expropriation?

Since most of the existing literature on business groups focuses on expropriation and tunneling, we devote some time to distinguishing the economic grounds of the expropriation incentive from our strategic reallocation incentive. One key idea in the paper is that central firms are special because they allow ultimate owners to control a large amount of assets in the business group. An alternative explanation is that this variable merely finds the firm which is used to extract assets from the business group. To test this idea, we identify the extractor firm in each group, and show that it is typically distinct from the most central firm (53% of the time) and we also show that the extractor firm does not predict returns in the same way as centrality. As a final check, we identify

"apex" firms, those firms in which the ultimate owner has the highest stake. This can be used as a proxy for the central firm. We find similar but weaker results using this proxy for centrality (the apex firm is distinct from the central firm in 24% of cases). This is sensible as our measure takes into account the entire network structure of the firm in identifying centrality, not merely the firm in which the ultimate owner has the largest stake.

Conclusion

We show that the position of a firm within a business group is important. In particular, central firms play a crucial role in allowing the ultimate owner to control a large share of the entire group. When their control is under threat, business group owners may strategically reallocate group assets to protect central firms in retaining control, thus changing the risk profile of these firms. Using a novel dataset of worldwide ownership for 2001-2013, we have shown that central firms are better protected in bad times. We have also documented lower expected returns for these firms. Overall, centrality helps to explain the cross-section of stock returns in the international market, thereby augmenting the explanatory power of traditional models.

Reference:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X21003792