The current fetish for big data is well known. Big data is being applied to many contexts ranging from transportation systems to health care. Our own interactions with many business leaders suggest that the greatest value from big data initiatives does not come from the ability to simply process and review a lot of data. Instead, it is the ability to integrate data from many different time periods and sources, and understand the implications of all that data.

The analysis of a large quantitative data set can uncover patterns, correlations, trends, preferences, and other useful information. However, to get a deeper understanding of what is really going on, a sharper focus is often useful. This involves collecting what we call "small data" and subjecting it to "smart analysis". For example, small data can help us to understand how and why a few professors are extraordinary in developing the knowledge and skills of their students, or when and why businesses create strategic alliances.

Professor Maris G. Martinsons

What is small data?

Small data is often largely qualitative. It is often collected through systematic observations and semi-structured interviews. Small data tends to involve a few informants and contexts, which are investigated deeply and intensively. Small data is usually rich data, involving detailed descriptions of such phenomena as: how people behave; how and why they react to specific circumstances; how they (attempt to) solve problems. Small data is most valuable if it is gathered and analysed very carefully.

Small data is often associated with case studies, but it can also be found in ethnographies, action research, and hermeneutic investigations. Business research based on small data typically has two distinct aims: 1) improving the performance of organisations and/or their stakeholders; and 2) contributing to theory and scholarly knowledge.

This belief in serving both the business and the academic community is rooted in our own backgrounds. One of us has an interest in the applications (and misapplications) of information systems. Wherever possible, he works with client organisations and stakeholders at all levels to solve their problems in a collaborative fashion. The other is an experienced management consultant who has consistently aimed to improve the performance of his client organisations. He has been driven by his intellectual curiosity to discover what really works to make different types of businesses successful.

To illustrate our application of small data, smart analysis 'method' in much of our research, we present two short cases. In each case, we first describe our data collection and analysis. We then explain how our smart analysis of the small data led to big impacts. Finally, we summarise the merits and challenges of this method for business research.

Professor Robert M. Davison

IT Applications for knowledge workers in China

As digital natives join the labour force, we have observed increasing tensions regarding information technology (IT) use in the workplace. Our first case focused on an international hotel chain's knowledge workers in mainland China. These workers regularly access social media applications such as QQ, WeChat and Weibo for work purposes even though these applications are proscribed by their own corporate policy.

Corporate policies, which often include permitted and restricted IT applications, tend to be formulated by business leaders. These leaders usually have a lot of business experience, but they are not very familiar with emerging IT applications. Not surprisingly, we have found that many leaders have little regard for informal IT-mediated communications media. They also worry about data privacy and security issues as personal digital devices proliferate. In contrast, digital natives view social media as essential tools for their jobs. They may aim to work around administrative and technological constraints in order to use these IT applications.

Outdated corporate IT policy?

Our research collected a variety of employeebased data. Over 14 months, we interviewed 27 knowledge workers (from middle managers to experienced non-management employees) in 12 hotel properties across 9 cities in China, and two executives from corporate headquarters. By studying a few knowledge workers in each location, we could compare the common problems and (sometimes) solutions of similar people in similar circumstances. Our interview questions covered topics including the nature of work, problem solving approaches, traditional and digital communications, corporate policies and culture. We often started with one question, such as "Which IT application(s) do you use?", but followed that up with many others: "Why this app?"; "What can this app enable us to achieve?"; "What is your boss' view regarding this app?"; "How was your corporate IT policy created?"; "What is the rationale for this policy?"; "Who was consulted when it was created?"; "Why were they (and not others) consulted?"...

We also reviewed the data logs showing the use of different IT applications. We built up a detailed profile of specific work needs, specific IT application needs, and how knowledge workers used different applications for different tasks at different times. We discovered that several specific solutions had been developed to circumvent the corporate IT policy.

With small data research, a basic set of questions may be an appropriate starting point for most situations. However, more specific, intensive and penetrating questions usually need to be asked in order to compile a richer picture. The aim is to describe and explain the current situation in such a way that an educated audience, unfamiliar with the context, can readily appreciate the nuances of the situation. Ideally, they would be able to recontextualise the findings to their own circumstances. An additional aim is to predict the consequences of potential future developments that the researchers foresee.

Conflict of the generations

By asking specific questions, we garnered a rich (but small!) data set focused on an investigation into the challenges and opportunities created by the situation of an IT governance structure that was mismatched with the employees' work-related requirements. Several key themes emerged from this study. They included: the digital expectations of the knowledge workers; the needs for knowledge workers to build and maintain personal connections (guanxi) with various communication partners, both internally and externally; the tensions between the stipulations of the IT governance structure and the espoused IT needs of the employees; and, perhaps most importantly, the tendency for employees to engage in acts of bricolage, accessing IT through unorthodox or proscribed channels, creating feral solutions to ensure the successful completion of work.

These themes, each illustrated with small qualitative data, formed the basis for an intensive case study. Subsequently, recommendations for better business practice were developed. They also facilitated the development of a new theoretical framework. This framework aims to explain how digital natives are likely to behave when IT governance structures conflict with their expectations for access to social media applications in the workplace.

Transforming the local operations of a multinational enterprise

The second case was an intervention in the local business of a multinational enterprise that specialises in IT-based solutions. One of us worked with an incoming local business leader in a concerted effort to achieve a business turnaround. The approach to achieve this dramatic improvement followed the traditional cycle of five action research stages: diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation, and reflection. This cycle is illustrated above.

When it comes to improving business performance, the key success factors are no secret. They include a clear vision and strategy, a fitness for change across the organisation, appropriate leadership and stakeholder incentives to motivate the change, and systematic processes to facilitate change. Nevertheless, the specific intervention will vary greatly. The plan will depend on what the diagnosis reveals as the root causes of the underperformance.

In this case, the multinational enterprise had entered the local market more than a decade earlier. However, the performance of this business had been consistently disappointing. This led to a steady stream of local business leaders being fired or resigning. The incoming leader was recruited from outside the industry, but he was under no illusion about the challenge ahead. He knew very well that he faced an uphill struggle in turning around his business in the face of keen market competition and customers who constantly demanded high-quality products and service.

Before taking on the project, the incoming leader and the professor both confirmed that the products sold by the firm were functionally competitive with its key rivals. However, we found that the customer services it provided to both businesses and consumers were poor. Corporate buyers claimed that they were 'treated like kings' by rivals. In contrast, many of those same buyers felt like they were 'almost as a nuisance' to some of the salespeople from the focal organisation. Based on some preliminary competitive intelligence gathering, we also discovered that that the business had been receiving 50 to 100 percent more consumer complaints than its main rivals in the local market. These complaints related to both after-sales service and technical support.

The action research philosophy meant that instead of conducting large-scale customer or employee surveys, the diagnosis concentrated on small data collection from key informants. Consistent with the well-known 80/20 rule, 20 percent of customers accounted for 80 percent of sales, and for 80 percent of complaints. It was critical to find out precisely what made them unhappy, and what was needed to make them happy. Similarly, one-on-one, face-to-face talks were conducted with employees. The primary aim was to understand their capabilities and motivations. Discovering this was not possible with any Big Data technique. It required careful, customised probing and the collection of somewhat subjective small data.

Turnaround plan

A deep diagnosis based on a foundation of small data from key stakeholders was completed after about 30 days of intensive effort. The diagnosis revealed three specific root causes of the service problems. Each of these problems was addressed as part of a turnaround plan that was formulated during the following month.

The plan included: tough decisions about which employees would be able to "ride the bus" as the business moved forward; exit procedures for those "leaving the bus"; specific training and development for those who would "stay on the bus", and also for those who would be hired; a small but systematic overhaul of the customer service process; and a sharper focus on a few key customers. Several corporate customers became 'prime targets' because they had large volumes of installed IT, and were expected to refresh their hardware soon.

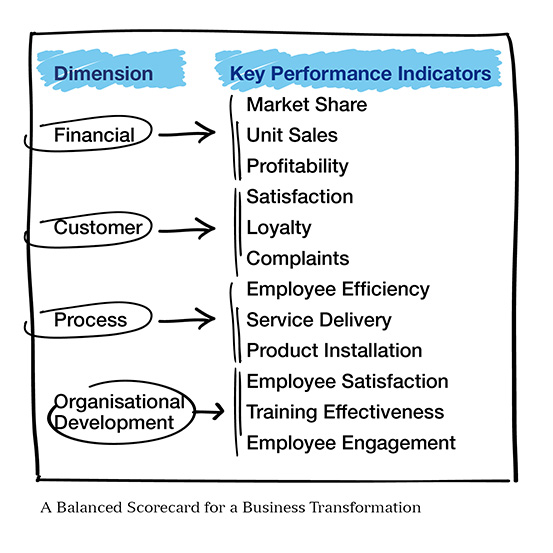

A balanced scorecard was designed specifically to monitor and evaluate progress as the plan was implemented. This initial scorecard included a dozen key performance indicators (KPIs) as shown the diagram below. The final set of thoughtfully-selected KPIs was based on fairly simple measurements: unit sales, customer service satisfaction, product performance, operational efficiency, and employee engagement. A composite indicator of organisational learning and development would also be monitored.

Smart analysis

The business leader set out specific targets for the sales, customer, and employee measures. These would subsequently be used to evaluate his performance. If the local business leader achieved all the targets, then his bonus would far exceed his annual salary. One target was to improve the ranking of the company in the local market from number 3 to number 2. The business leader privately desired and expected his business to be number 1.

The business plan for the local operations and the resources needed to implement it were rigorously reviewed and approved by top management at global headquarters. The plan included some short-term initiatives to steady the local business and harvest some 'lowhanging fruit'. These also aimed to build up employee morale. Nevertheless, the ambitious elements of the plan extended over several years. It required substantial resources to modify and expand the local office, launch a major marketing campaign, make better use of technology and, most importantly, to hire and develop dozens of employees.

Implementation of the plan began about three months after the new leader took command of the local business. Frequent evaluation of the KPIs in the months that followed confirmed that the business was steadily improving. A few major customers were acquired while existing customers complained less often about the service that they were receiving. These developments were reflected in 2 of the KPIs: unit sales and customer service satisfaction.

By addressing the root causes revealed by the small data diagnosis and smart analysis, the performance of the local business of the multinational firm steadily improved. Within one year it had gone from third to first in the local market.

Sustained improvement

The huge improvement exceeded almost all expectations. It justified a celebration to reward everyone who had contributed to this remarkable success. In parallel, a personal touch was used to reflect on the actions and achievements to date. This reflection made this remarkable case useful for both illustrating and theorizing about best practices in business transformation and organisational change management. The successful boss and the action researcher also had lengthy discussions on how to sustain this enviable level of performance. Further opportunities for improvement were also considered. Since the boss was likely to receive a well-deserved promotion to a regional role, the next round of diagnosis, planning and execution would be undertaken by a new local leadership team.

Conclusion

We have illustrated how researchers, working with business managers, can make big impacts with small data and smart analysis. While conducting research for many decades, we have found many organizsational situations that are suitable for small-and-smart research. It commonly results in major contributions to academic knowledge and business practice. Some small data research may be limited to thoroughly describing and theoretically explaining a specific situation. Other projects include a carefully-planned intervention based on smart analysis that usually brings about substantial improvements in performance. This in turn often leads to the discovery of transferable management practices.

A key to the success of most small data, smart analysis projects is the cooperation of organisational champions. These business people commonly have some of the same intellectual curiosity that inspires and motivates our own professional endeavours. Our preferred type of research is undeniably challenging because it involves the messiness of real-world organisations and human interactions. The success of these projects often hinges on the commitment and support of top managers in the focal organisation – that is where the relationships and networks of CityU business school alumni and professors can be very helpful.