Professor Wenyu Dou of Marketing discusses how decentralised e-commerce trading platforms promise to lower transaction costs, increase reliability, and promote frictionless trade. After a kaleidoscopic tour through marketing innovation in world history, he asks how profound a change blockchain is likely to make?

Business trends change fast. In 2017 artificial intelligence arguably won out, but 2018 has unquestionably been the year of blockchain. Along with the various cryptocurrencies – it has been a hands-down winner. Blockchain is now being spoken of as the most revolutionary technology since the advent of the internet itself. From smart contracts to cryptocurrencies it has, supporters claim, the potential to transform multiple business processes. But this is far from the world's first disruptive technology. Over five thousand years ago, cuneiform script invented in Mesopotamia was one of the first recording mediums in ancient trade. In the mid-18th century industrial revolution, the rise of steam engine technology increased the possibility of mass-scale industrial production. So what kinds of opportunities and challenges will blockchain technology bring to industries? Is it really the Disruptorin-Chief that some authorities are making out?

Early writing tablet recording the allocation of beer, probably from southern Iraq, Late Prehistoric period, 3100-3000 BC

© BabelStone / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Features of blockchain technology

A few basics: Blockchain is a decentralised technique for data storage, verification, delivery, and communication. In a blockchain network system fraudulent behavior is rejected and suppressed by distributed blockchain nodes through the constraints of cryptographic algorithms. Blockchain technology allows participants to create a unified and transparent information record system, without the prior need to establish a trust relationship or endorsement through centralised institutions. Each new block is generated strictly in chronological order in the chain. Because of the irreversibility of time, data fraud can be easily traced and rejected by subsequent nodes. Immutability is therefore one of the main advantages of blockchain.

In the context of e-commerce, blockchain technology has the potential to eliminate the dependence on intermediaries. It enables barrier-free circulation of information and facilitates transactions between buyer and seller. In terms of economics, blockchain technology promises to reduce transaction costs.

Transaction costs

The issue of transaction costs had been recognised for centuries, but was first elaborated by Chicago-based British economist, Ronald Coase in “The Nature of the Firm” in 1937. From the perspective of consumers, transaction costs refer to the total cost that the buyer pays for a transaction in addition to the price. This may include time, energy, as well as other subjective factors such as psychological stress.

Generally, transaction costs may be categorised into three factors: Search and identification costs – the cost of identifying the appropriate seller and product; negotiation costs – the cost of communication and negotiation for the transaction detail, including delivery date, payment method, etc. and enforcement costs – the cost of safeguarding buyers' own rights and interests. Should a product not match specifications as laid out in the contract, this is the cost needed to protect the consumer's rights.

Take an everyday household product such as soap as an example. Fast-moving brands such as LUX or Dove may occupy a prominent position in the supermarket, and loyal customers typically find them without difficulty. Search and identification costs are at a minimum. But e-commerce platforms present a different scenario. On Etsy, an e-commerce platform dedicated to merchandising handmade, vintage, and unique goods, a search for “handmade soap” produces 46,000 results. Identifying the personalised soap of your choice may take time. It comes at a price.

Marketing and transaction costs

Things have come a long way since the Paleolithic Age more than 100,000 years ago when early humans first got together and lived in tribes. Commerce developed from the exchange of spare food/produce, and transaction costs were almost zero.

But by the Neolithic Age, some 10,000 years ago, people had started to migrate long distances and agriculture civilisation developed in fertile areas. In Mesopotamia, one of the earliest civilisations, city-states were established. With this more complex organisation, the transaction costs of “international” trade doubled compared to those of the simple tribal barter. Some historians suggest that the appearance of cuneiform script was an attempt to recode complex transactions and contracts and reduce those transaction costs.

According to cultural anthropologist Alan D. Eames, the world's first beer advertisement was discovered in Mesopotamia: “Drink Elba, the beer with the heart of a lion”. This advertisement successfully established the first brand image of beer, reducing the search and identification costs to buyers, as well as the negotiation and enforcement costs.

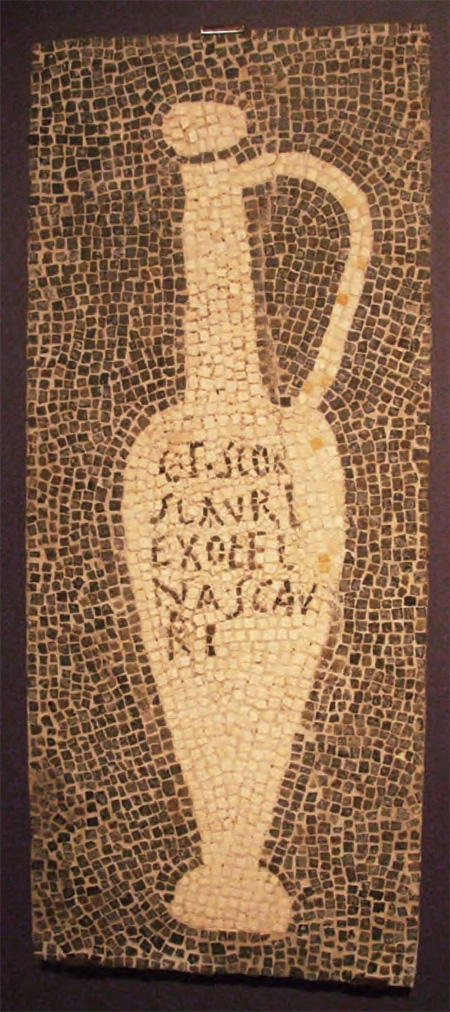

Garum, a fermented fish sauce used in the cuisines of ancient Rome

© Claus Ableiter / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Brand awareness was also established in Roman times in the era of Pompeii. Umbricius Scaurus, the largest mackerel sauce merchant in ancient Rome, won more than 60% of the market with his brand slogan sealed on the bottle: “Best Fish Sauce. The flower of garum, made from mackerel, a product of the manufactory of Scaurus”. The fish sauce proved popular beyond Rome and was sold as far afield as France.

The early establishment of brands helped reduce transaction costs, but the subsequent development of a fully-fledged retail industry was to create yet greater efficiencies.

The world's first department store Harding Howell & Co opened in the Pall Mall district of London in 1796

© Mary Evans Picture Library

Markets, trade shows and fairs had existed for more than a thousand years, but the unsettled nature of early marketplaces implied high consumer transaction costs. In ancient Rome, trade took place in the forum. Trajan's Forum was a vast expanse, comprising multiple buildings with shops on four levels, and arguably the earliest example of a permanent retail shop-front. Specialised trading areas were an innovation and helped create more competitive pricing. In 13th century England, an arcaded walk in the town of Winchester was established by several cloth stores. “Drapery Row” provided protection against the weather and helped create a more pleasant shopping experience. By the 17th century, permanent stores had expanded from a factory outlet to a multi-category retail store. The world's first department store Harding Howell & Co opened in the Pall Mall district of London in 1796 offering a convenient shopping experience for the new middle class of the industrial revolution. Meanwhile, search, negotiation, and enforcement transaction costs were all reduced.

Trajan's Forum, the earliest known example of permanent retail shopfronts

© Alessio Nastro Siniscalchi / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-2.5-IT

In the second half of the 20th century, new types of retail formats evolved. Supermarkets, category killers such as IKEA, warehouse stores, and discount stores such as TK Maxx emerged. By this stage, sellers' perception of brand awareness had become prominent, and in practice they applied several proficient approaches to decrease transaction costs, such as brand equity and endorsement strategies.

Nowadays, e-commerce is bringing a massive shakeup to the retail industry, witness boarded up shops in town centres all over the western world. Online sales platforms such as Amazon, Taobao and Airbnb are penetrating all markets, providing stiff competition to high-street and department stores. The main feature of e-commerce platforms is to attract traffic and popularity by encouraging “long-tail”, small and medium-sized sellers from all over the world. Many sellers on the platform are start-ups or individuals, so search costs are higher for buyers.

In the contemporary business environment, traditional strategies such as the combination of brand and third-party endorsement which used to reduce transaction costs have encountered challenges on e-commerce platforms. So, what kinds of advanced technology can be applied to improve platform performance?

E-commerce contributes to the destruction of town centres. Boarded up shops in Rotherham, the UK

© Simon Dack / alamy stock photo

Discount stores such as TK Maxx are important players in the out-of-town retail parks

© David Holt / CC-BY-SA-2.0

The future of blockchain and e-commerce trading platforms

The main advantages of blockchain technology are its transparency and immutability which can be used to protect data authenticity as well as to create trust. The main challenge of reducing transaction costs for buyers on e-commerce trading platforms involves identification (search) for the seller, negotiation - reaching an executable, non-objectionable agreement, and the resolution of any after-sales disputation. At present, some start-ups, such as Soma and CanYa, are developing e-commerce trading platforms based on blockchain technology which promise to solve these challenges.

Identification

Blockchain technology can provide a unique digital ID to verify the background and identity of the merchant (as well as the seller) on an e-commerce platform. Take Provenance, an e-commerce platform based on blockchain technology as an example. Assuming that an organic cherry seller has the certificate issued by an official association, Provenance will confirm the seller's identification and place it on the blockchain network using algorithmic instructions. The information is transparent to buyers from all over the world and cannot be altered. So, if the certification expires on 31 December, 2018, the seller cannot change it to 31 December, 2019.

Negotiation

The decentralisation of a blockchain e-commerce platform eliminates the role of third-party endorsement, making communication between authorised buyers and sellers more efficient. But there's more. Smart contracts can automate the process of generating contracts. For example, if a buyer wants to purchase 5 kg of organic cherries at HKD300/kg from a seller, then they can set up a smart contract. If the buyer receives the cherries in 3 days, HKD1,500 will be transferred to the seller's account. The entire transaction process requires no supervision or management of an intermediary organisation, and the contract is automatically executed. After the transaction, the buyer can also provide comments on the seller, and the information is publicly displayed on the blockchain. Those reviews can reduce transaction costs for future buyers.

Disputation Resolution

Currently, blockchain e-commerce platform offers two approaches to solve transaction disputation. The first one is an escrow service. Say, there is a pre-set escrow account in the smart contract, and the buyer pre-deposits HKD1,500 there. When the deal is confirmed, the buyer will give the order to transfer HKD1,500 from the escrow account into the seller's account. But if the quality of the cherries does not meet the buyer's standards, the HKD1,500 will be returned to his account. Although the operation of an escrow service seems similar to Taobao's, it does not require the intervention of a third party.

Another solution is that buyer and seller set up a different type of smart contract involving a disputation mediator from the blockchain e-commerce platform. Should a dispute about the quality of the cherries arise, the mediator has the right to review the details of the contract and to make an arbitration. In turn, after the mediation, buyer and seller can review the mediator's ability on the blockchain. Such an evaluation will help to establish the mediator's reputation on the platform. The organiser of the blockchain e-commerce platform can provide certain incentives and compensation for the mediation job. Again, there is no involvement of a centralised platform.

| Amara's Law |

|

Roy Charles Amara was an American researcher, scientist, futurist and president of the Institute for the Future best known for coining Amara's law on the effect of technology. His adage states:

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

This law has been described as encouraging people to think about the long-term effects of technology and has been described as best illustrated by the hype cycle, characterised by the "peak of inflated expectations", followed by the "trough of disillusionment". The law has been used in explaining cyber-attacks and nanotechnology. Wikipedia

|

Decentralised architecture – low costs

The role of the organiser on a blockchain e-commerce platform is limited to technical structure and planning. The organiser does not participate in the transaction directly, and the platform essentially operates by itself. This decentralised architecture means management costs are kept to a minimum, and the organiser only needs to charge the seller a low maintenance fee.

The blockchain e-commerce platform described above is only one possible scenario and the technology is developing rapidly. Amara's Law suggests that the uptake of innovative technologies is likely to be slower than people's expectations and comes with tremendous challenges, not least usage inertia and loyalty to traditional e-commerce platforms.

A record 168.3 billion yuan was spent during China's annual "Double11" retail event

© South China Morning Post

From a technological perspective, the ability to handle massive transactions may still be questionable. Tmall's “Double 11” 24-hour shopping event, for example, attracted more than 140,000 brands and hundreds of millions of consumers in November 2017. Suspicion from government and regulators, as well as competition from traditional platforms may also represent a continuing challenge. But in the long-term Amara's Law warns us not to underestimate the impact of innovative technologies.

A version of this article was first published in the Financial Times, China edition on 7 August 2018.

Professor Wenyu Dou

Professor

Department of Marketing