Professor Jeff Hong is Chair Professor in the Department of Economics and Finance and Department of Management Sciences at City University of Hong Kong. He received his PhD from Northwestern University in 2004. Prior to joining CityU, he was Professor and Director of Financial Engineering Laboratory at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Professor Hong's research interests include business analytics, operations research, and financial engineering. He has published extensively in leading academic journals in business areas, and has won several prestigious awards from international academic societies. Professor Hong enjoys reading history and economics in his leisure time.

The Forbidden City, Beijing

Photo courtesy of Pixelflake, via Wikimedia Commons

In early March 2015 a documentary film on China's air pollution, Under the Dome1, attracted a huge amount of public attention. Within the first three days of its release it had been viewed more than 150 million times on the Internet. It has since occupied the headlines of major media platforms and triggered furious debate. The film, produced by Chai Jing a prominent Chinese journalist and popular TV anchor, took a personal angle to look at China's air pollution issues and especially PM2.5 pollution. This particulate matter, with diameter less than 2.5 micrometers, is one of the most dangerous types of air pollutants, because the particles are so small that they can penetrate into our lungs, enter our blood stream and cause many diseases such as lung cancer and heart attacks.

This was not the first time that PM2.5 had attracted media attention. For most Chinese people the term PM2.5 had never been heard of before 2008, and was not linked to the deteriorating air quality in big cities. But in 2008, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing set up a Twitter feed reporting PM2.5 levels on their roof top in real time. The numbers soon shocked the general public because they indicated the air was not only heavily polluted but sometimes toxic. Public attention finally pushed the Chinese government to report real-time PM2.5 readings in 2012 and to look at the issue more seriously.

The instance of a documentary film produced by a celebrity and drawing huge public attention is not new to us who have worked on environmental issues. In 2006 the former U.S. Vice President Al Gore released a documentary film An Inconvenient Truth2 addressing global warming and climate change issues. The film occupied media attention and triggered much debate in the U.S. and abroad, and certainly helped the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Al Gore to win the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. Sadly, however, the global warming issue remains with us today and very little progress has been made globally since 2006. So, in fighting China's air pollution, what can we learn from the unsuccessful experience in combating global warming?

Global Warming

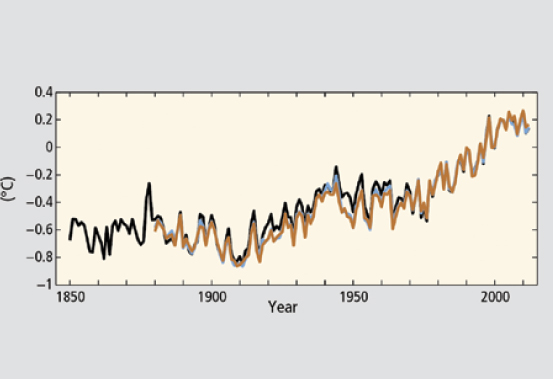

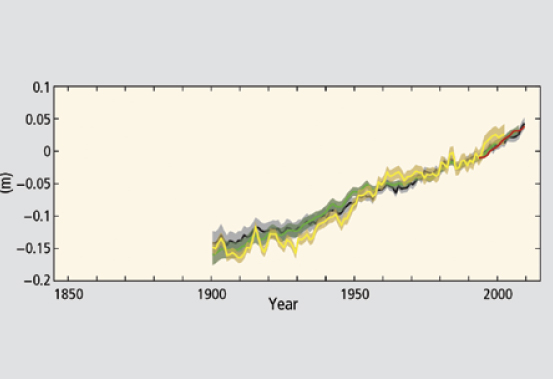

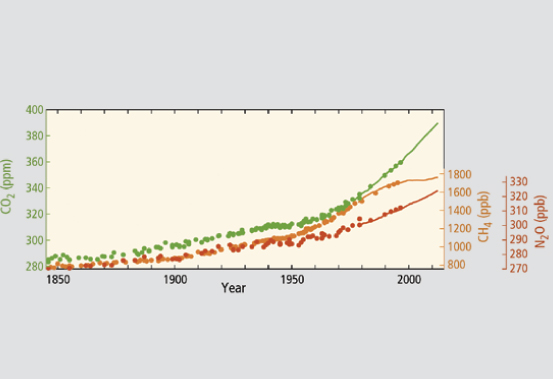

Is our global climate system warming? There are multiple strands of scientific evidence supporting this argument. In Figure 1 we extracted some statistics from the latest IPCC assessment report3. One can see clearly that there has been an increasing trend in global temperatures in the past century and, consequentially, the globally averaged sea level has also risen significantly during this period. However, scientists are still debating whether this global warming was caused by human activity and, in particular, the burning of fossil fuels since the industrial revolution. It is clear from Figure 1 that the burning of fossil fuels, including coal, oil and natural gas, has caused a drastic rise of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, and it is also supported by scientific experiments that the increase of CO2 concentration can cause greenhouse effect and lead to higher temperatures. However, our global climate system is very complex and we can never conduct experiments at this level to prove the linkage with 100% confidence. Therefore, in its assessment report, the IPCC concluded that "most of the observed increase in globally averaged temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations."

"To slow down or to stop global warming, we have to restrict greenhouse gas emissions."

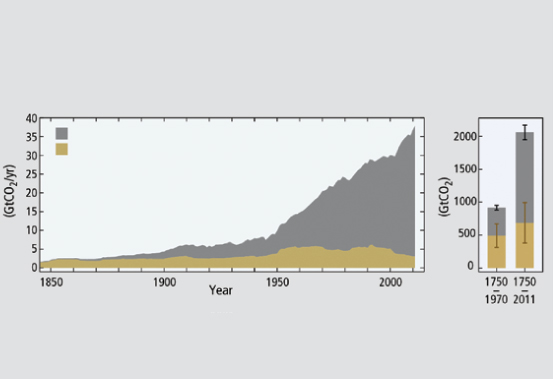

Therefore, to slow down or to stop global warming, we have to restrict greenhouse gas emissions. The earliest attempt to do so dates back to 1992 when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was developed. Aimed at stabilizing global greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, UNFCCC organized a series of negotiations among its 196 state parties to form protocols which may set binding limits on greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol adopted in 1997 was a first important step forward. Parties involved in the protocol, who collectively accounted for 85% of greenhouse gas emissions, committed to reducing emissions to an average of five percent against 1990 levels within the first commitment period from 2008 to 2012. 37 industrialized countries and the European Community agreed to binding targets, but the U.S. which was the largest greenhouse gas emitter at the time, did not ratify the protocol. As of 2012, only about half of these countries had achieved their targets. And of these many were east European countries, whose achievement may be attributed to significant economic downturn after revolutions in the early 1990s, rather than active environmental controls. Most importantly, the Kyoto Protocol failed to stop or slow down the increase of the global greenhouse gas emission, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Statistics from IPCC Synthesis Report 2014 - part 1

Figure 1. Statistics from IPCC Synthesis Report 2014 - part 2

Figure 1. Statistics from IPCC Synthesis Report 2014 - part 3

Figure 1. Statistics from IPCC Synthesis Report 2014 - part 4

The situation was even worse when it came to the second commitment period. The Copenhagen Summit was held in 2009 to try and attain a consensus on a climate change mitigation framework beyond 2012. Despite the presence of many world leaders, including the U.S. President Barak Obama and China's Premier Wen Jiabao, the results were disappointing. Although an agreement for the second commitment period from 2012 till 2020 was finally reached at the United Nations Climate Change Conference, known as the Doha Amendment near the end of 2012, only 36 countries agreed to binding targets up to July 2015, while acceptance of 144 countries is required to activate the agreement. As for the world's largest emitters, China participated in both commitment periods but did not accept any binding targets, while the U.S. has not ratified either treaty.

The IPCC projects that by the end of this century the global temperature will rise 1.8℃ to 4.0℃ relative to the 1980-1999 level. This may impact significantly on everyone who lives on earth. To use Ms Chai Jing's term, we are all living under the same dome. Reducing greenhouse emissions and slowing down global warming are beneficial to all of us and all countries. So why is it so difficult to reach an agreement?

Prisoner's Dilemma

The industrial revolution conventionally dates from the invention of the steam engine by James Watt in the late 18th century. The critical breakthrough was the ability to transform fossil energy into mechanical energy. Since then the world has changed dramatically and global energy consumption has increased more than 20 times. Today, fossil fuels account for over 80% of the world's primary energy use, and they are the foundation for economic development and quality life styles. Therefore, we have to understand that, in many cases and regions, the right to burn fossil fuels – and with it the right to pollute – goes hand-in-hand with the right to economic development. To control the emission of greenhouse gases often implies controlling economic growth. This is sometimes difficult to accept, especially for developing countries where millions of people fight against poverty. For them, issues such as global warming or air pollution are perhaps too remote to care about. This explains why it is often people from more developed regions who are active in environmental issues and also explains why it is middle- and upper-class Chinese living in big cities who have started to care about air pollution. To handle the environmental issues, we have to recognize this tradeoff between economic development and emissions and to understand that people from different regions and different classes have different incentives and priorities.

To make the issue more complicated, greenhouse gases are global pollutants, meaning that emissions from a particular region affect not only that region but the entire world. For local pollutants, such as soil pollution or water pollution, one country (or region) often has the incentive to invest to clean them up because the people who bear the cost are the people who benefit. For global pollutants, however, things are very different. One tendency is to rely on other people cleaning them up; then it is possible to enjoy the benefits without paying the costs. The consequence is that everyone wants to take a free ride and no one wants to pay the bill. This is very similar to the famous Prisoner's Dilemma in economics, where both prisoners are punished because they do not collaborate, but yet they will not collaborate (See box below).

Moreover, in the case of global warming, the incentive to stop it and the ability to do so are sometimes misaligned. Here are some examples. Firstly, island countries such as Tuvalu in the mid-Pacific, are most affected by rising sea levels, and actively seek a solution to global warming. However, their voice barely counts in global negotiations because of their small size and limited bargaining power. Secondly, developed countries often have more money and more advanced technology to handle climate change. For instance, global warming causes adverse weather conditions and this has a direct impact on agriculture. Rich countries have more advanced technology to protect their crops or may use money to buy food from global markets, while poor countries have to rely almost solely on weather. Thirdly, large countries such as the U.S., China and Russia are big greenhouse gas emitters, but their very size presents some advantages in handling climate change. For instance, some have argued that Russia might even benefit from global warming because the retreat of Arctic ice will provide access to more resource-rich land, and a new and shorter trade route connecting Europe and Asia.

The direct consequence of this prisoner's dilemma is that we see many proposals and a lot of blame games in worldwide climate change negotiations. The following are some of the (hypothetical) proposals and their critics. They will help us understand the difficulties in reaching a global agreement.

- Uniform cut: every country reduces greenhouse gas emissions by the same percentage. This proposal favors developed countries that have a large share of the current emissions and thus more room for improvement. They have better technologies so they can move heavily polluted manufacturing to developing countries and adopt nuclear and renewable energies. Moreover, this proposal gives developed countries permanent advantages, so that they can pollute more than developing countries.

- Uniform per-capita target: every person on earth should have the same right to emit a certain amount of greenhouse gases. This proposal favors developing countries because the present per-capita emission of developed countries may be several times bigger than that of developing countries. Setting a uniform per-capita target means that many of the developing countries do not need to do anything, while the developed countries have to reduce significantly. Given the huge population of developing countries, this proposal may not lead to any reduction at a global level.

- Historical considerations: The current global warming situation is caused by developed countries. For instance, the shares of the U.S. and countries of the European Union in global cumulative energy-related CO2 emissions between 1890 and 2007 are 28% and 23% respectively, while the developing countries, including China and India, emitted only 30% combined. Therefore, when setting emission targets, some argue that historical contributions should be considered and developing countries should be allowed to emit more.

- Carbon intensity: greenhouse gas emission per unit of GDP. Some countries, such as China, are in favour of carbon intensity when setting emission targets because they believe economic growth should be encouraged. For instance, China has set its goal to reduce carbon intensity by 40-50% by 2020 from the 2005 level. However, some argue that, given China's fast economic growth, this seemingly impressive target will not help reduce China's greenhouse gas emissions. To give an example, suppose that China's GDP grows at an average rate of 8% per year during 2005-2020 and the carbon intensity is reduced by 50% by 2020, it still means that China's total emissions in 2020 are 60% higher than that of 2005.

- Carbon footprint: the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions caused by manufacturing a product. Some argue that emission targets should not be set according to a country's carbon emissions but to its carbon footprint. This takes into account the recent globalization process where some countries have become specialized in manufacturing and tend to have greater greenhouse gas emissions. But, the argument goes, these emissions should not be counted towards them because the products are not consumed by them. Therefore, some of the emissions are transferred to consuming countries (this is termed carbon transfer) and the manufacturing countries are not deemed responsible for these emissions.

All of these proposals make sense, but so do arguments put forward by their various critics. This brief overview demonstrates the complexity of global warming issues. We believe that, without the willingness of leading countries to give up their individual interests and collaborate to maximize global social welfare, it may be impossible to reach a global agreement that is both fair to all countries and efficient in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.

Prisoner's Dilemma

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The prosecutors do not have enough evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They hope to get both sentenced to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to: betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. Here is the offer: If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison. If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa). If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge). The following table summarizes the payoffs:

| |

Prisoner B stays silent (cooperates) |

Prisoner B betrays (defects) |

| Prisoner A stays silent (cooperates) |

Each serves 1 year |

Prisoner A: 3 years Prisoner B: goes free |

| Prisoner A betrays (defects) |

Prisoner A: goes free Prisoner B: 3 years |

Each serves 2 years |

Here, regardless of what the other decides, each prisoner gets a higher pay-off by betraying the other ("defecting"). The reasoning involves an argument by dilemma: B will either cooperate or defect. If B cooperates, A should defect, since going free is better than serving 1 year. If B defects, A should also defect, since serving 2 years is better than serving 3. So either way, A should defect. Parallel reasoning will show that B should defect.

Excerpt from Wikipedia

Back to China's Air Pollution

When we look at China's air pollution issue, we are forcibly struck by the similarities with the global warming issue. Firstly, PM2.5 not only affects local regions but also surrounding regions. They are acting like global pollutants in China. In the winter of 2013, PM2.5 caused heavy smog not only in northern cities, but also cities in the eastern regions such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Hangzhou, and cities in southern regions such as Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Therefore, no single city or province would be able to solve this problem alone.

Secondly, China's economic development is not balanced. Cities like Beijing and Shanghai have a per capita GDP4 that is almost four times higher than that of poor provinces such as Guizhou and Gansu. Therefore, people from different regions also have different opinions on the importance of air pollution. People living in the rich coastal regions of China are more concerned about air quality and air pollution, whilst people living in poor rural regions may care more about lifting themselves from poverty and improving their standard of living.

Thirdly, the regions with the most PM2.5 emissions may not be the more developed regions. They may not have the technologies and/or the economic incentives to reduce emissions. According to a study conducted by Tsinghua University and the Asian Development Bank in 2013, seven of the most polluted cities in the world were in China. They are Taiyuan, Beijing, Urumqi, Lanzhou, Chongqing, Jinan and Shijiazhuang. Besides Beijing and Jinan, all are from the less developed regions of China. Many of these cities are the centres of coal mining and electricity generation. They supply coal and electricity to Beijing and other more developed coastal regions, and struggle to develop their economies into other sectors.

Fourthly, as with global warming, there are historical considerations and carbon transfer which may be taken into account. Developed regions have historically polluted more than many of the less developed regions, and people living in developed regions certainly consume more products – and therefore have a greater emission footprint – than those living in less developed regions.

We have also seen many blame games in China's air pollution. For instance in Under the Dome Chai Jing blamed the burning of coal in China. She stated:

"Do you know how much coal was burned in China? It was up to 3.6 billion tons in year 2013. Do you know how much coal was burned outside China in this world? Our number is larger than the sum of others. Such consumption of coal last time happened in British in 1860s. They paid a destructing cost afterwards. Therefore, many other countries reduce and control their burning of coal after the Great Smog in 1960s. China, however, just started the reform and open policy and demanded large energy to take off. The coal was chosen... Where is the coal burned in China? In 2013, 380 million out of 3.6 billion tons were burned in Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei. 300 million out of the 380 million tons were burned in Hebei."

From these lines, we can feel her anger towards coal burning in China, especially in Hebei province where Beijing is centrally located. However, are there alternatives? An economy of China's size requires a huge amount of energy supply to sustain and to grow. At this moment, it has to depend on fossil fuels, such as coal, oil and natural gas. We are already very lucky that China has a huge reserve of coal which has powered China's economic growth for the past three decades. Of course, coal is not as clean as oil and natural gas, but China lacks these cleaner fuels and has to buy them on international markets. If China is going to replace coal with oil, the oil price in the international market will soar. Moreover, it is unlikely that China can secure the oil supply given its current international relations and its political and military power.

Ms Chai mentioned the British experience in countering air pollution. But to secure its oil supply, the British government has historically used a range of foreign policy strategies. For instance in 1920, because of the discovery of oil in the region of Mosul, the British moved it into the newly formed "State of Iraq" despite the independence request of the Kurdish people living in the region. This eventually led to one of the most conflicted regions in today's world, and currently Kurdish troops with U.S. air support are fighting a war against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) in the region. Again, in 1953 the British overthrew the democratically elected Iranian prime minster, Mohammed Mossadeq, in order to secure its oil interest in Iran, and the leading British oil conglomerate, the British Petroleum Company (BP), was the result of the coup d'état. We wonder if Ms Chai knows about this side of British history.

Escaping the Prisoner's Dilemma

Despite the many similarities between global warming and China's air pollution, we believe there is a crucial difference. In the case of global warming, IPCC can only serve as a facilitator in climate change negotiations, and has no real power over individual countries. In the case of China's air pollution, however, China has a strong central government that can not only coordinate effectively the interests of different regions, but also enforce policies that maximize social welfare on a country-wide level.

This is not the first time the Chinese government has faced an environmental problem on this scale. Before PM2.5, acid rain was once the most important environmental issue in China. Acid rain is a rain or any other form of precipitation that possesses elevated levels of hydrogen ions, a low pH level in other words. It can have harmful effects on plants, aquatic animals and infrastructure. Emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide which react with water molecules in the atmosphere to produce acids, are the main cause of acid rain. Again, the problem was caused by burning coal for electricity and, this time, because coal consists of a large amount of sulfur and burning coal produces sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide.

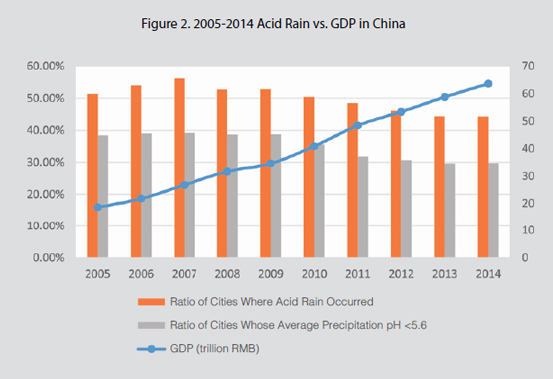

The Chinese central government has made a tremendous effort in solving the acid rain problem in the past 10 years. China has developed the most advanced desulfidation technologies in the world, and deployed them in coal power plants. According to Figure 2 with the data extracted from the Report on the State of the Environment of China from 2005 to 20145, the number of cities where acid rain occurred decreased from 51.3% to 44.3% in the period, along with a sharp drop in the number of cities whose average pH value was lower than 5.6, from 38.4% to 29.8%. These numbers may not look impressive at first glance. However, it is important to note that China's GDP grew more than three times during the same period. Taking the economic development into account, the improvement is indeed encouraging. The successful experience in fighting acid rain proves that the Chinese government has the capability to handle environmental issues and we are confident that the PM2.5 problem can eventually be solved.

Photo source: AFP Photo

Figure 2. 2005-2014 Acid Rain vs. GDP in China

What Can We Do?

As people living in China, we are not only the victims but also the contributors to China's air pollution problems. Instead of blaming others, we need to look at ourselves and take greater responsibility. There are typically two ways to reduce air pollution. The first is to reduce energy consumption, and the second is to use cleaner energy. Much has been talked about reducing energy consumption, such as using public transport, driving less, setting air conditioner to a reasonable temperature, etc. These are of course very important. However, here we want to emphasize the second way.

Besides fossil energy, there are nuclear energy, and renewable energy such as solar, wind, water etc. However, renewable energy is in general too costly and limited to certain regions. Therefore, we have to focus on nuclear energy. And there has been a lot of debate on the use of nuclear energy. For ordinary people like us, because of high profile accidents such as the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the then Soviet Union, and the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan, our first impression is that nuclear power plants are dangerous and we do not want to live anywhere close to them. In Hong Kong, this has been much discussed in recent years, because there will soon be nine nuclear power plants in neighbouring Guangdong province. Are nuclear power plants dangerous? In the most lethal Chernobyl accident, the number of direct deaths was 56, while in the Fukushima accident, it was 2. However, in 2013 alone, 1,049 workers were killed in coal mines in China and a decade ago, in 2003, the number was as high as 6,434. Therefore, it is not hard to conclude which one is more lethal. Of course, for most of the readers of this magazine who are middleand upper-class city dwellers, mining accidents are remote and the risks of nuclear power plant accidents are more real. But when you compare the number of people who suffer from heavy air pollution – for instance in Hong Kong more than 3,000 premature deaths were attributed to air pollution in 2013 alone – and those who may be affected by nuclear accidents, it still seems to make sense to replace at least some of the old coal power plants by nuclear ones.

In Hong Kong our air quality is worrisome. But we have to understand that it is us who are mainly responsible, instead of the neighbouring mainlanders. The three major sources of Hong Kog's air pollutants are electricity generation, navigation and road transport. According to the statistics provided by the Environmental Protection Department of Hong Kong SAR Government, the three sources accounted for 97% of Hong Kong's sulfur dioxide, 85% of nitrogen oxides, and over 70% of suspended particles (including PM10 and PM2.5)6. On 18th February 2012, The Wall Street Journal published an article, named "No Easy Scapegoat for Hong Kong Pollution"7. It pointed out that Hong Kong's average level of nitrogen dioxide, a key air pollutant that makes people cough, ranked No. 2 among 32 major Chinese cities, and was worse than Beijing. The pollution was mainly caused by Hong Kong's aging buses and ships entering and leaving Hong Kong's ports. There are a lot of things that Hong Kong government can do, but the article concluded that "Hong Kong's government is lagging behind the mainland [in controlling air pollution]" and "Hong Kong needs to do more to address local pollution on its own."

Photo source: China Daily