Professor Peter Burke is Emeritus Professor of Cultural History at Cambridge University. Professor Burke studied at Oxford, taught at the new university of Sussex in its early years (1962-79) and then migrated to Cambridge, where he was Professor of Cultural History until his retirement and where he remains a Fellow of Emmanuel College. His bestknown books include Culture and Society in Renaissance Italy (1972), Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (1978), The Fabrication of Louis XIV (1992) and The Social History of Knowledge (2 vols., 2000 and 2012).This article is an abridged version of the City University Distinguished Lecture given by Prof Burke in November 2014.

Innovation is not just a concern of the worlds of business and technology but of universities as well. The cover story of one edition of The Economist last year discussed the reinvention of the university under the heading Creative Destruction1. The point was to comment on the rise of MOOCs (massive open online courses). You can see them from one point of view as a challenge to the traditional university, and on the other hand as a solution to the rising cost of more traditional education.

Going beyond universities, is the age of invention over? What kinds of people innovate? What kind of environment best supports them when they are putting forward their creative ideas? To answer questions like these there is a need for both international and interdisciplinary collaboration. Contributions to the theory of innovation have been made by economists such as the Austrian Joseph Schumpeter who invented that phrase Creative Destruction, sociologists such as the Italian Vilfredo Pareto, geographers such as the Englishman Peter Hall who wrote about Creative Cities, psychologists such as Liam Hudson, philosophers of education such as Donald Schön, urban theorists such as Richard Florida, and management theorists such as Ikujiro Nonaka. Sometimes the specialists talk to one another, sometimes they don't. The British economist Chris Freeman, my ex-colleague at the University of Sussex, used to criticise his colleagues in economics for neglecting innovation in technology and organization, so there does seem to be a need for an interdisciplinary overview.

A modern day view of Florence. In the 16th century city, everywhere was within a 15 minute walk.

Professor Peter Burke

The spinning mule hybrid hugely revolutionized the production of cloth

Photo courtesy of Welcome Trust, via Wikimedia Commons

Traditions of innovation?

I look at the process of innovation from an historian's point of view. Traditions of innovation, a seemingly contradictory concept, have been particularly impressive in the past. But we can learn from the past how to break with the past. A well known example from the early years of the British industrial revolution is the sequence of inventions or at least improvements that helped to make the production of cloth more efficient: the spinning jenny evolved into the spinning frame, and then in turn into the spinning mule, the last a hybrid of the other two.

Another example of sustained innovation is that of painters in Florence in the 15th and 16th centuries. There were no art schools as there are today. The way to learn was to become an apprentice to an established painter, helping him in his workshop, emulating him. It is possible to identify whole chains of masters and apprentices over the centuries, and yet there are a number of Florentine painters who managed to establish a distinctive style of their own, most obviously Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo amongst many others.

A third example comes from a group of French historians in the 20th century called the Annales School, who founded a journal in 1929 to launch their innovative ideas2. They are still active. Four generations of these French historians have now collectively produced some of the most innovative historical work in the world. So the obvious question is: How could they maintain this tradition? The success of the group in over 80 years is linked to a certain style of intellectual leadership, which allows the followers to go their own way within certain limits, and discourages them from simply reproducing the ideas of the leaders. The fact that there were two leaders rather than one, Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, contributed to the flexibility of the movement. Indeed Febvre deserves a special mention for choosing a successor, Fernand Braudel, who disagreed with him on certain important questions, notably the place of free will in human history. An open style of leadership, then, produced strong disciples. These examples may help us confront the crucial question, what is innovation?

Like creativity – the propensity to innovate – innovation itself is difficult to define. If we take a closer look, innovation often turns out to be an adaptation of an earlier idea, technique, or organization. It may be a free or creative adaptation, but it is an adaptation all the same. Think of the printing press. Gutenberg came from the Rhineland, so he was extremely familiar with the wine press, which he adapted for printing books.

Painting with a sculptural quality: The Creation of Adam, in the Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

Michelangelo

Innovation by collaboration

Turning to the history of ideas, Donald Schön suggests that new ideas come into existence by extending or displacing old ones. Charles Darwin's theory of evolution borrowed something from the population theorist Thomas Malthus, and something from the geologist Charles Lyall, and produced something new. Innovation is a kind of bricolage, a kind of collaboration between dead and the living. But of course innovation also emerges from collaboration in the present, especially in face to face groups. Hence the title of a 2003 book: Group Creativity: Innovation through Collaboration3 and this point about adaptation has serious consequences for the central problem: what conditions encourage the process of innovation?

To translate the question into Schön's terms, what conditions encourage displacement? Some are psychological conditions inside the heads of individuals and groups, others are social or cultural. Of course it is important to draw distinctions between different domains: art, religion, business, also science, and technology. In these domains, innovation might take place in different ways. Collective attitudes to innovation also vary with cultures and with historical periods. In certain periods innovation was considered at best unimportant, and at worst positively wrong-headed. In art and religion in particular, tradition used to be appreciated, whilst innovation was rejected. Religious innovators such as Martin Luther had to disguise their innovation, presenting their ideas as a return to the past: So, renovation, not innovation; reformation as re formation. In a similar fashion, artists and architects revived styles as with the neo-classical or gothic revival. It is only in the last 120 years or so that artistic vanguards and new religions no longer pay that kind of tribute to the past.

In this short article I will be thinking across the various subject domains, and focusing instead on social units: individuals, small groups, institutions, social milieux, and finally cultures. First I will identify certain obstacles to innovation and finally conditions that are favourable to it.

Habit – an obstacle

"Habit is as firmly rooted as a railway embankment in the earth. – Joseph Schumpeter"

To turn the question upside down, what are the obstacles to innovation? Joseph Schumpeter once said, "Habit, is as firmly rooted in ourselves as a railway embankment in the earth." A certain way of doing things comes to seem natural. Individuals are often unaware of possible alternatives to their own tradition. If subversive ideas occur, they may be repressed, a kind of unconscious self-censorship. It was thanks to his awareness of these obstacles that Schumpeter put forward the famous idea of creative destruction, viewing it as the essence of capitalism, and as a kind of permanent revolution from within. Originally formulated to analyse economic history, this idea is capable of a much wider application. In similar fashion, the Swedish geographer Torsten Hägerstrand has argued that the process of innovation always has a negative side as well as a creative side. He called the destructive side 'denovation' as opposed to innovation4.

Collaboration can take time. The Neo-Gothic facade of St Maria del Fiore, Florence, was completed in the late 19th century – some 450 years after the Cathedral's consecration

Systems of Censorship: The Inquisition Tribunal

Francisco de Goya

In talking of innovation and institutions there is a paradox because their whole point is continuity, to make sure that the contribution of individuals and small groups outlives them. Many institutions such as Oxford University and the Catholic Church, have a long history of discouraging innovation. In 16th-century Oxford, a group was formed known as the 'Trojans' because they opposed the new idea of studying ancient Greek. As for the Church, its proud motto was 'semper eadem', always the same. Systems of censorship have often been introduced to suppress new ideas. Even institutions designed precisely to innovate, can lose their openness or fluidity. They congeal, encouraging the people who inhabit them to become the prisoners of routine or habit. They can congeal fast, thus producing diminishing intellectual returns.

Whole cultures can go the same way, discouraging innovation. Spain was deeply creative in the Middle Ages, but from the 1490s onwards turned increasingly inwards: The expulsion of the Jews and the Muslims, the introduction of the inquisition, the ban on studying at foreign universities in case Spaniards became infected with the wrong kind of ideas, all of these events ensured that a remarkable series of innovations came to an end.

"Creative destruction – the essence of capitalism, a permanent revolution from within."

The blessings of setbacks

In a recent book The Innovators: The Blessings of Setbacks the Dutch anthropologist, Anton Blok suggests that individuals who become famous as innovators are not necessarily more talented than their colleagues. Instead, they work harder, sometimes obsessively so. Why? Because they have had to overcome setbacks: coming from a poor background, or losing their parents at an early age. Innovators are usually outsiders, geographically often provincial, psychologically often loners, so intellectually they take more risks, having less to lose. Success depends on factors such as whether or not they find a patron5.

The economist J.K. Galbraith suggested that outsiders have a detachment from conventional wisdom often aided by physical distance from the place where that wisdom was produced6. Exiles and expatriates play a crucial role. They view the knowledge systems of their host country with foreign eyes. If they remain abroad long enough, they sometimes see the knowledge system of their original country with foreign eyes as well. Among the most perceptive discussions of intellectual detachment are those of Central European sociologists; the Hungarian Karl Mannheim who fled from Hungary in 1919, went to Germany, fled again in 1933 and went to England, and his German assistant in Frankfurt Norbert Elias who joined him in exile in London in 1935.

Nomad intellectuals

There is also a certain kind of disciplinary displacement; nomad intellectuals who can even be seen as renegades. These nomads train in one discipline and work in another. They take along a cast of mind from the old discipline and in adapting to the new one, notice things in the second discipline things that had not been discovered before. For example, Vilfredo Pareto trained as an engineer carried over with him his ideas in dynamic equilibrium into his work first as an economist, then as a sociologist. Again, the English biologist, John Maynard Smith, who was trained as an engineer, used his engineering skills in his study of the evolution of the flight of birds.

When problems need to be solved, it has been argued that cognitive diversity is even more important than ability. Two or three points of view are better than one7. This implies a critique of the common emphasis on innovation as the work of individual geniuses. The popular mythology of innovation is dominated by these individuals – artists, scientists, philosophers, inventors, or as Schumpeter liked to emphasise, entrepreneurs. These geniuses, Leonardo da Vinci in his workshop, Rene Descartes in his stove, Isaac Newton under his apple tree, are all assumed to be solitary individuals thinking creative thoughts when they are alone. But my reading of history suggests exactly the opposite.

Adam Smith virtually invented the subject of economics. His statue in Edinburgh

Discovering DNA

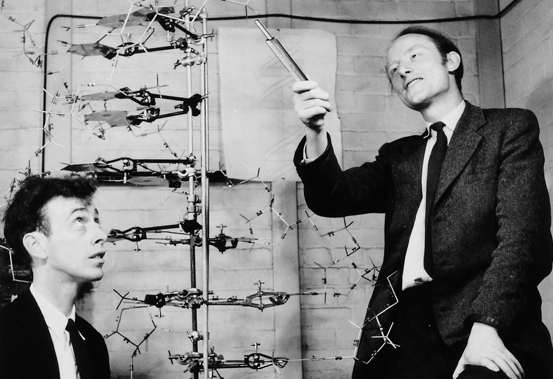

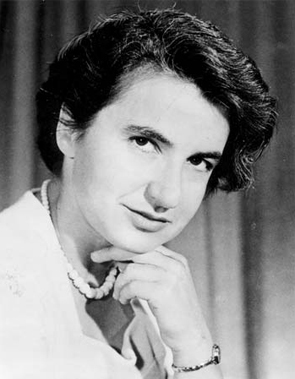

I believe the propensity to innovate is a collective as well as an individual phenomenon. It depends on interaction and exchange even if some individuals contribute more than others to the processes. Take the case of the discovery of the double helix. It has been mythologized as the work of Francis Crick and James Watson, but they were not alone. They were competing in a race against time with the American chemist Linus Pauling. They were working with a colleague Maurice Wilkins who eventually shared the Nobel Prize. And they gained crucial information from the crystallographer Rosalind Franklin, the so called "dark lady of DNA," who did not get the credit which she deserved for the collective discovery, at least at the time. So, here, as so often, the locus of innovation was the small group, ideally with common interests but different approaches, often educated in different countries or coming from different disciplines.

In the academic world the locus of creativity is often the seminar or institutes of advance study where people from different disciplines can meet daily for six months or a year. I owe a great debt to both the Princeton Institute and to its counterpart in Berlin the Wissenschaftskolleg.

Innovation as a collective phenomenon - the discovery of DNA. From left: James Watson and Francis Crick

Photo source: A. Barrington Brown / Science Source

Innovation as a collective phenomenon - the discovery of DNA. James Watson and Francis Crick's colleague Maurice Wilkins

Innovation as a collective phenomenon - the discovery of DNA. The crystallographer Rosalind Franklin

Photo courtesy of Jenifer Glynn

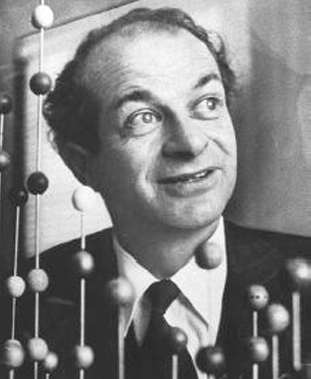

Innovation as a collective phenomenon - the discovery of DNA. James Watson and Francis Crick's their American competitor Linus Pauling

Clubs, cafes and bars

Informally the role of clubs is very important especially in the English speaking world. Adam Smith virtually invented the subject of economics when he was talking to merchants in the political economy club in Glasgow. It was an interesting exchange between the practical knowledge of merchants and the philosophical knowledge of Smith. In other countries informal exchanges have taken place in cafes or bars, regularly frequented by a group of friends with common interests, what the Spanish call a tertulia. It was a great institution in Spain at the turn of the 20th century. A special table would be reserved for this group of friends and they would meet on a certain day of the week, so that the proprietor knew they were coming. Drinking – especially drinking in public – is a great stimulus to creativity, lubricating the speech and making possible an intellectual jam session. So, cafes and bars are part of what has been called the soft infrastructure of innovation, helping to generate the flow of ideas and inventions.

Take the example of London in the late 17th and early 18th century, and the proliferation of coffee houses in which customers not only read newspapers but they conversed. Some houses specialized in particular kinds of conversations. Lloyds was the place to find merchants. Child's and Garraways were the places to find what we now call scientists, then known as natural philosophers. Wills was the haunt of poets.

Something similar existed in Vienna in the early 20th century, when it was famous for cafes. One of them hosted a discussion group in the philosophy of science that met every Thursday, and included Otto Neurath, the founder of an interdisciplinary movement for unified science.

Nowadays, as the management theorist Nonaka tells us, certain Japanese firms have established talk rooms where researchers are expected to discuss one another's work whilst drinking tea. And some of these firms also hold sessions at inns at the weekend. The normal rules of discourse differ greatly from those dominant in the workplace. Hierarchy temporarily disappears. The atmosphere is egalitarian. It allows new ideas to flow along with the sake8. Alcohol is a great remover of inhibitions. In this way small groups support individual innovators and are sometimes responsible for innovation itself.

Can institutions innovate?

So the next question is, what supports the small group? So we come back to formal institutions as the hard infrastructure. Some of them are purpose built, specifically founded to foster innovation. In the United Kingdom there is a government department for Business Innovation and Skills. In Australia there is a department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research. I am a bit sceptical as to whether these departments have made a great contribution to innovation. In my view, indirect approaches are more likely to succeed than direct ones.

Outside universities there are government think tanks, whilst discoveries made in private laboratories may not be made public, to keep information from rivals. Educational institutions also have a role to play. Universities that were once designed for the transmission of tradition since the 19th century have reinvented themselves as centres of innovation. But the problem with permanent institutions is that routinization often comes to replace creativity. If he were alive, Schumpeter might suggest that there is a need for creative destruction in this domain.

The most effective way of promoting innovation would not be to try and reform old institutions, since they often have a great capacity for resistance. I think it is more cost effective to found new institutions. I mentioned earlier the Annales School of French historians founded in the University of Strasbourg. It was an old university, but after World War 1, when it was transferred from Germany back to France, Bloch and Febvre found themselves in effectively a new university.

The Third Place - soft infrastructure of innovation. A boisterous London coffee house, circa 1668

Photo source: Lordprice Collection / Alamy

New universities – magic moments

In England seven new universities were founded in one go in the 1960s. The first of them was the University of Sussex. The ambitious Mission Statement at that time was to redraw the map of learning, and to do this by encouraging interdisciplinary approaches even at the undergraduate level. I learned from this experience that a new institution is often accompanied by what might be called a "magic moment of creativity." One reason for this is that the new institution is small enough to allow for face to face groups of diverse individuals to form. Another is a sense of solidarity among newly appointed groups of teachers, often young, and committed to new ways of doing things. But I also learned from my time at Sussex that magic moments come to an end. Routinization takes over, although in history there are significant exceptions, such as 15th century Florence.

Creative cities

Beyond all these institutions is the city. Big cities in particular have been described as incubators of human creativity, or hubs of creative revolutions. The geographer Peter Hall devoted a large book to creative cities in history9: ancient Athens, Renaissance Florence, Enlightenment Paris and London, Vienna at the beginning of the 20th Century. One reason for the importance of cities for innovation is the concentration of institutions, especially universities. Another is that they act as a magnet for immigrants, people with different ways of looking at the world from the local population.

Displaced people can contribute to the displacement of ideas. Vienna before 1914 saw innovators such as Freud, Wittgenstein, Mahler, Klimt, the architect Adolf Loos, the novelist Robert Musil, and most of them came from the provinces, drawn to what was then the capital of a multilingual, multicultural empire. After 1919 Vienna declined into the capital of a small state and has not been closely associated with innovation since then.

Talent, technology and tolerance

"For cross fertilization to take place, the refugees had to be welcomed. The culture as a whole had to be an open one."

Or take the famous case of the migration of central European scientists and scholars, most of them Jewish, most of them German speaking, going to the United Kingdom and America in the 1930s. The Germanic culture of method and theory, encountered the more empiricist Anglo-America tradition. This encounter led to lots of misunderstandings, but in the long run it turned out to be extremely creative. In fields as different as physics, sociology and art history, some theory rubbed off on the English, and a greater respect for empirical evidence rubbed off on some of the Germans. Of course numbers and critical thresholds were very important here. A few immigrants might be accepted or assimilated by the host culture. But in certain small subjects like sociology or art history in Britain in the 1930s, the critical mass of the refugees was sufficient to shake up the system and produce innovation. For this cross fertilization to take place, the refugees had to be welcomed and given a home. The culture as a whole had to be an open one. This was true of the Dutch Republic in the 17th century or England in the 18th century, the converse of the closed culture of inquisition Spain in the 16th century, or Japan's closed door in the early 17th century. So there is a need for cultures to be open and tolerant. That is the third of Richard Florida's 3 conditions of innovation the 3Ts10. He talks about Talent, Technology and Tolerance. But the example of Renaissance Florence reminds us of a fourth condition – a culture of competition – maybe equally necessary for innovation. It may make life less pleasant, but it does have a creative effect.

The shock of the new: The Louvre Pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre Museum, Paris

Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, by Gustav Klimt

The Buzz

A final reason for the importance of cities in the process of innovation is that they offer the spaces of sociability – the ecological niche, in which small discussion groups flourish, leading to what some people call the buzz. One bright idea stimulates another one. There was a lot of buzz in Renaissance Florence, Enlightenment London, fin de siècle Vienna. Even in the age of the internet, face to face communication remains indispensable. In an age of urbanization it is comforting to discover that a city is still a creative milieu, a new idea in one domain encouraging innovation elsewhere. Yet again displacement, but the effectiveness of cities depends on their size; not too small, not too large. Renaissance Florence at its peak was a city of less than 100,000 people. Enlightenment London less than one million, and of course the creative centre, the place where you could find all these discussions going on, was very much smaller. The larger the city, the greater the dispersal of homes, and then the traffic problems discourage the kind of intellectual sociability out of which new ideas, magic moments, have so often come. I hope that these reflections on innovations in the past will increase consciousness of alternatives in the present, alternatives to the way that we happen to be doing things now. Such an awareness of alternatives is itself a precondition for innovation.

- ^Creative Destruction:

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21605906-cost-crisis-changing-labour-markets-and-new-technology-will-turn-old-institution-its

- ^Burke, P. (2015) The French Historical Revolution: the Annales School, 1929-2014, 2nd edn Cambridge: Polity Press.

- ^Schön, D. (1963) The Displacement of Concepts, Tavistock Publications; Paulus, P., & Nijstad, B.(Eds.), (2003) Group Creativity: Innovation through Collaboration. : Oxford

University Press.

- ^Schumpeter, J. (1942), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, New York, Harper's; Hägerstrand, T. (1988) 'Some Unexplored Problems in the Modeling of Culture Transfer

and Transformation', in P. J. Hugill and Dickson, B.D. (Eds.) The Transfer and Transformation of Ideas and Material Culture, College Station TX, 217-32.

- ^Blok, A. (2013) De vernieuwers, English translation The Innovators: the blessings of setbacks, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2015.

- ^Galbraith, J. K. (1958) The Affluent Society, Cambridge MA, Riverside Press.

- ^Page, S. (2007) The Difference, Princeton University Press.

- ^Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The Knowledge-Creating Company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation, Oxford.

- ^Hall, P. (1998) Cities in Civilization, Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Cf. Andersson, D. et al. (Eds.)(2011) Handbook of Creative Cities, Cheltenham: Elgar.

- ^Florida, R. L. (2002).The rise of the creative class: And how it's transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.