After a century of marginalisation, Central Asia transit routes are once again taking centre stage. City Business Magazine editor Eric Collins investigates the nature of the historical Silk Road, and asks why China is unveiling a new version for the 21st century.

A romanticised early 20th century vision of the Silk Road – The Bazaar in Samarkand, by Alexei Vladimirovich Issupoff, showing a Kazakh couple arriving by camel

Photo Courtesy of Sphinx Fine Art, London

Sinuously the Silk Road flows from ancient times down to the present. From China through the Taklamakan Desert to Samarkand at its centre, through the grassland steppe of Central Asia to the shores of the Mediterranean, it helped pioneer globalisation. Romantically we imagine spices, silks, perfumes and precious stones wending their way by camel between China and Europe. But what was the nature of this Road? Who and what travelled along it and in what direction? Was it just confined to goods? Or did ideas make the journey as well? How Broadband was this historical Silk Road? And how does it relate to its latter-day successor, the recent China development policy initiative, One Belt One Road (OBOR)?

Geographically, the Silk Road was certainly broadband. The original term for the Road coined by the late 19th century German explorer Ferdinand von Richthofen, "Seidenstraßen", was in the plural: "Silk Roads". So it is more accurate to think of a network fanning out in many directions, rather than a single route. It travelled through an astonishingly diverse range of landscapes; travelling westwards from Xi'an it traversed the Gansu corridor, before reaching the oasis town of Dunhuang. Further west travellers had to decide whether to circumnavigate the Taklamakan Desert to the north or south in the frontier lands of Xinjiang, before converging at Kashgar. The routes then split again, one reaching southwards over the Karakorum highway into present day Pakistan, others fanning out over the grasslands of Central Asia; Persia, Mesopotamia, Russia and onwards to the Mediterranean and Europe.

A wall painting from the Chinese Temple Shrine, Penang, Malaysia, showing one of the ships of Admiral Zheng He. In the 15th century, China became increasingly interested in the wider world, exploring the Indian Ocean and the coast of Africa

© RM Encyclopedia © Corbis

An ancient road

The Silk Road has been around for a long time: In the 3rd century BCE, Alexander the Great travelled along it from Greece as far as Samarkand, before turning southwards into India. In 138 BCE the Chinese Emperor Wudi of the Han Dynasty opened up the north west by sending the famous mission of Zhang Qian as far west as the Kingdom of Dayuan, beyond Kashgar. Sogdians and Chinese at either end of the eastern Silk Road exchanged numerous trade and diplomatic missions in the 6th century. At various times different peoples vied for supremacy over parts of the route: Tibetans from the south, Mongolians from the north, Chinese from the east and Arabs from the west sought influence in the 7th and 8th centuries. Genghis Khan waged an almost unstoppable programme of conquest, and emerged as the undisputed master of the Mongolian steppes by the early 13th century. Mongol influence caused disruptions as far west as Krakow in Poland, in Baghdad, and in the north of China and encouraged the growth of maritime trade before the age of the Portuguese seaborne empire. Some of these voyages are well known such as Admiral Zheng He's early 15th century exploration of the Indian Ocean and the coast of East Africa. The overland Silk Road fell into relative disuse after the Ottoman Empire boycotted trade with the West in 1453. By that time the maritime route pioneered by the Chinese, the Portuguese, and later the Dutch and the British was coming into ascendancy.

The Mongols swept across Asia with astonishing speed. Genghis Khan emerged as the undisputed master of the Mongolian steppes in the 13th century

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Goods and gifts

Not all trade along the Silk Road was global, much of it being local and subsistence in nature. And it was not really a "Silk Road": most of the silks found in Ancient Rome were from the Byzantine Empire, not East Asia. Silk did however travel along the Road but primarily as a currency, rather than as finished goods exported from China to Europe. There was a massive transfer of wealth to the north west frontier of Tang Dynasty China, as payment for the soldiers stationed in these distant regions, and this was paid for in bolts of silk which was the currency of choice. In this region the Silk Road was a string of oasis towns, and between these was traded more basic goods such as wheat, flour, aromatic spices, sugar and brass.1

The Silk Road was also well known for carrying "official" gifts. Horses from the grass lands of Central Asia were much sought after in China, partly because they roamed free and were stronger than their smaller Chinese counterparts. The "heavenly horses" from the Ferghana valley in Uzbekistan were the most highly prized. As Jared Diamond has noted, it is relatively easy for plants and animals to spread along a line of latitude.2 And there are multiple examples of successful migration: Apples from the steppe belt in Russia spread in both directions, oranges from China to the Mediterranean world; and grapes to China.

Trade was regulated and from at least the time of the Han Dynasty travel passes needed to be presented at regular checkpoints. In return, according to the 14th century explorer Ibn Battuta, "China is the safest and best country for the traveller. A man travels for nine months alone with great wealth and has nothing to fear."3

Vermeer's Young Woman Reading a Letter at an Open Window portrays the results of global trade in the mid-17th century. The fruit bowl in the foreground has the distinctive blue and white patterning of Asian ceramics

© RM Imaginechina

Inventions, philosophy, beliefs

But the Silk Road was as much famous for the ideas that travelled along it as the goods. News of inventions spread along the route; famously the Chinese invention of paper during the Han Dynasty, and in the 6th century the invention of printing. The oldest known book is of the Buddhist Diamond Sutra from the 9th century, discovered in the Dunhaung library cave. The British scholar Joseph Needham has chronicled in detail the transmission of such mechanical and other techniques, and the time lag — sometimes centuries — before their adoption in the west.4

The Road was also a conduit for philosophy and beliefs. As early as the 6th century BCE, Zoroastrian fire worshippers lived in Persia, and the powerful trading people, the Sogdians, who bound together the disparate parts of the Silk Road, were originally Zoroastrians. Vestiges of this tradition can be seen in fragments of illustrated scriptures from the Uighur culture of the mid-8th century near present day Turfan.5

The Silk Road was also the route through which Mahayana Buddhism first entered China, witness the temple of the Buddhist protector Vaisravana at the ancient kingdom of Khotan, east of Samarkand, and the extraordinary cave art at Dunhuang.6 Later, Islam was also to spread eastwards, inspiring a host of beautiful buildings such as the Madrassah at Samarkand.

The Madrassah at Samarkand. Muslim influence inspired many ornate buildings along the Silk Road

Plague

It was not just trade and ideas that travelled along the Silk Road. Along with the goods came a downside: disease. None was more destructive than the 14th century Black Death that ravaged both Asia and Europe causing a catastrophic decline in populations. The plague spread rapidly reaching Constantinople in 1347 and the cities of northern France in 1348 killing, by one contemporary estimate, nine tenths of the population. In an early form of biological warfare, Mongols laying siege to the Genoese trading post of Caffa in the Crimea suffered an outbreak of plague. Turning a crisis into an opportunity they placed corpses in catapults and lobbed them over the city walls into the city in the hope that the intolerable stench would kill everyone inside. The terrified Italian merchants fled back to Europe by ship, carrying the plague with them.

"In conjuring up the ethereal Silk Road, von Richthofen unwittingly created a brand with global potential"

Maritime Silk Road

To the south, the Maritime Silk Road was the main conduit, complementing the land routes especially in times of disruption. By the late 13th century the city of Guangzhou had become the main point of China's imports and exports. A shipwreck from this time reveals goods being imported from all over southern Asia, and probably the Persian Gulf and East Africa too, including pepper, frankincense, glass and cotton.7 The recent 2008 discovery of the early 17th century Selden Map ( 東西洋航海圖 or Nautical Chart of the Eastern and Western Seas) in the Bodleian Library of Oxford reveals the extent of Ming Dynasty seafaring ambitions. China appears squeezed into the top left portion of the map, whilst shipping routes are marked towards the islands of East and Southeast Asia which take up more than half the map. China is no longer presented as a self-sufficient entity at the centre of the world. Ming Dynasty China emerges as vigorous and export orientated.8 Later in the 17th century, the Qing Dynasty lifted restrictions on foreign trade, leading to a surge in Chinese exports of tea, Chinese sugar and porcelain. This helped inspire a new tradition of Dutch ceramics at Delft, dealing in the distinctive blue and white porcelain of the East.9

The Roads were a complex network of trading routes which evolved over time on land and at sea. Interestingly, Ferdinand von Richtoffen reduced this complexity to a single red line on the map of the Silk Road dating from 1877. Perhaps this was because he was charged by the German Reich to map an appropriate route for a railway line between Berlin and Beijing, an early example of infrastructure ambition in Central Asia. But the Silk Roads are best thought of in the plural. And in conjuring up this ethereal concept, von Richthofen had hit upon a marketer's dream: He had unwittingly created a brand with global potential.

Vaiśravaṇa, the Buddhist Guardian of the North and a deity of wealth associated with the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Khotan, located on the southern branch of the Silk Road that ran around the Taklamakan Desert

© The Trustees of the British Museum

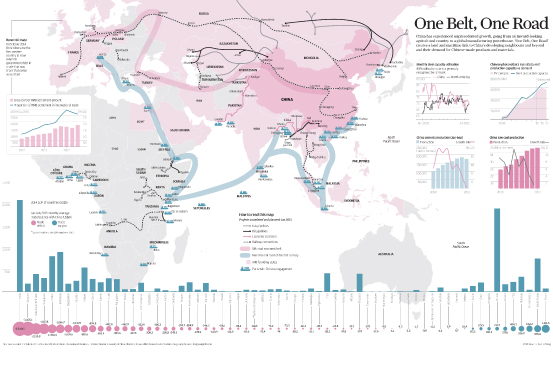

One Belt One Road

It is no surprise, then, that the Silk Road has re-emerged in the 21st century, most recently as a leitmotif in a development policy initiative emanating from Beijing: One Belt One Road. How should we understand this latest reincarnation? Chinese economic influence has been felt the world over during the past couple of decades, but in terms of foreign policy, the nation has remained remarkably low-key. That has now changed with President Xi Jinping's October 2013 announcement of the One Belt One Road policy10 which formalised China's regional policy strategy. China is reshaping foreign policy relations for the 21st century: So turning from history to the present day, we may ask: how broadband is this new version of the Silk Road? Is it just about economics, or are there more factors at play?

One Belt, One Road

© South China Morning Post

The spirit of the Silk Road

Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st century Maritime Silk Road, by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), released in March 2015 emphasises the benign evolution of an ancient tradition:

Symbolizing communication and cooperation between the East and the West, the Silk Road Spirit is a historic and cultural heritage shared by all countries around the world. In the 21st century, a new era marked by the theme of peace, development, cooperation and mutual benefit, it is all the more important for us to carry on the Silk Road Spirit in face of the weak recovery of the global economy, and complex international and regional situations.11

Another analysis is that OBOR is a macroeconomic policy, China's way of exporting itself out of an economic slowdown.12 There is massive overcapacity in steel-making and concrete, so the argument goes. Infrastructure buildout is saturated at home. It is time to "go west", with massive rail, road and bridge projects connecting to the states of Central Asia, and onward to Europe. This overland thrust is complemented by the maritime road along which ports have been constructed in countries such as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan, the so called "String of Pearls" strategy.

Marshall Plan

Those with a 20th century historical vision see something akin to the United States post-World War II Marshall Plan. OBOR is no less than a geopolitical strategy designed to cement Chinese influence in the region. Along the way it will bring increased wealth to the provinces of the west. China's western region and its central Asian neighbours contain vast reserves of oil and gas. OBOR is set to drive a huge swathe through the Xinjiang region, a desert region that has 22% of China's domestic oil reserves and 40% of its coal deposits. Here, a poorer Muslim Uighur population has been increasingly restive in recent years. So there is an opportunity to share a more connected future, and at the same time work to ameliorate any threat of radical Islam. Like the Marshall Plan, OBOR has a geopolitical mission, and is similarly ambitious in scope, covering dozens of countries with a total population of over 3 billion people.

Broadband Silk Road

There is another thesis, and this would place OBOR as the latest chapter in the ongoing road to global integration. Ever since the 1972 visit of US President Richard Nixon to China, and more especially the era of Deng Xiaoping, China and the West have been moving inexorably towards a closer understanding at national and institutional levels. The steps have been multifarious, the movement gradual: China's creation of four special economic zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen in 1980; China's membership of the World Bank in 1980; the designation of 14 open coastal cities in 1984; China's accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001; the introduction of revised accounting standards in 2006; and the opening of the Shanghai Pilot Free Trade Zone in 2013, to name but a few key moments. Public Private Partnerships may be seen to represent the latest chapter in this narrative of integration through which China and the West are building an evercloser understanding.

But the Silk Road was always more about people than political organisation. And massive movements of people across the globe continue. According to the latest data from China's Ministry of Education, 459,800 Chinese students went abroad in 2014, an 11.1% increase over the year before. Meanwhile the logistical outbuild is forever expanding: pipelines, container ports, bridges and railways, as the web of international communications is woven ever closer. Train times between Chongqing, China and Duisburg, Germany are down to 13 days. Trains half a mile-long wind their way across desert, plain and grassland. Where once the camel patiently padded across the desert sands, wheels of steel screech their way along the 21st century Silk Road.

- ^Hansen, V. (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press.

- ^Diamond, J. M. (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton. Chicago.

- ^Frankopan, P. (2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. Bloomsbury.

- ^Needham, J., & Wang, L. (1954). Science and civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press.

- ^Whitfield, S. (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. The British Library.

- ^Bentley J. (1993). Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Time. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^Frankopan, P. (2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. Bloomsbury.

- ^Hongping Annie Nie. The Selden Map of China. Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

- ^Frankopan, P. (2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. Bloomsbury.

- ^The concept originated in a 2009 proposal submitted by former deputy director of China's State Administration of Taxation Xu Shanda to the Ministry of Commerce: http://finance.sina.com.cn/china/hgjj/20090806/07566578273.shtml

- ^http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/201503/t20150330_669367.html

- ^http://thediplomat.com/2015/06/the-trouble-with-the-chinese-marshall-plan-strategy/