Today’s Initial Coin Offerings share many of the characteristics of the early European stock markets. The value of the offerings is difficult to assess, the regulatory regime is in its infancy, and the market is more concerned with speculation than longterm sustainability. Historically, the chaos of the 17th century Dutch Tulip Fever and the early 18th century new world speculations – the English South Sea Company Bubble, and the French Mississippi Bubble – set the scene for tighter regulatory measures and the establishment of centralized financial institutions designed to create trust.

In this brief sketch, we look at the three early stock market speculations, and trace the evolution of central banking through to the early 21st century, and their role as monetary managers. The story closes with national jurisdictions once again seeking to cope with turbulence on the financial markets, this time associated with the emergence of new technology. Nation states and private sector companies alike are attempting to establish standardized approaches as they seek to leverage and control blockchain’s distributed ledger technology.

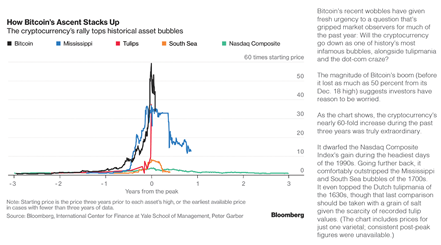

How Bitcoin's Ascent Stacks Up

Tulip Fever

When the tulip arrived in Europe from the Ottoman Empire (to which present day Turkey is the closest successor state), the flower’s popularity soared and it quickly became a must-have for the newly wealthy merchants of the Dutch Golden Age. At the same time a virus began to infect the bulbs, producing variegated and spectacular effects in the bloom but fatally weakening the bulbs. A speculative frenzy was triggered between 1634 and 1637. The disastrous fallout was chronicled at the time by a number of Dutch satirists, including the work of Jan Brueghel the Younger featured on the centre pages of this magazine. What could be more misguided than investing in a collection of tulip bulbs?

South Sea Bubble

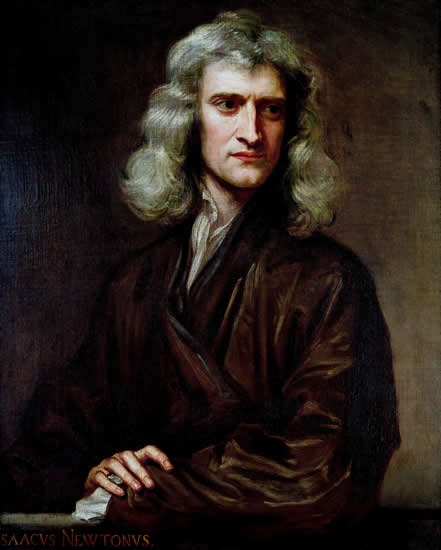

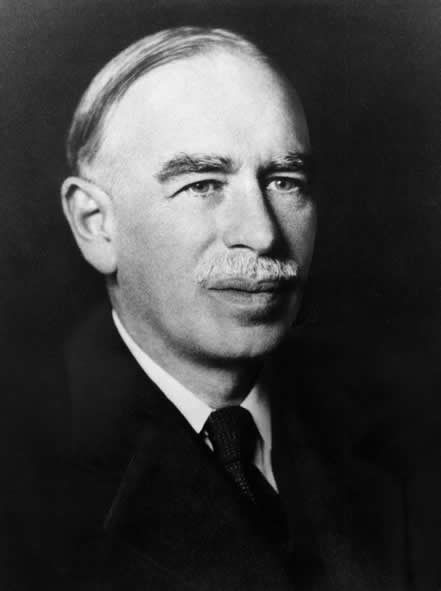

Isaac Newton, who lost most of his life’s savings in the South Sea Bubble

© Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo

"I can calculate the movement of stars, but not the madness of men"

Tulip Fever may have bankrupted a few investors in the Dutch Republic, but the long-term fallout was limited. Financial speculation, however, was moving closer to matters of state. A problem common to all European nations of the time, was how to finance war. In 1690 the British were defeated by the French navy, a catastrophic blow! The navy had to be rebuilt, and the name of the Governor of the newly founded Bank of England was put on the subscription to a new loan. Under the terms of the Royal Charter of 1694, the bank issued banknotes that were backed by gold. But future wars needed greater finance.

In the early 18th century, Britain was involved in the War of the Spanish Succession. Various schemes were put forward to reduce the national debt as an alternative to the Bank of England. In 1711, the South Sea Company, a British joint-stock company was founded and granted a monopoly to trade with South America and nearby islands. The company stock rose greatly in value on "the most extravagant rumours" of The Battle of Beachy Head, 1690. The French gain control of the English Channel. How to pay for a new British navy? The Headlong the value of its potential trade in the New World. After hitting a peak of expectations in 1720, it collapsed to little above its original flotation price. Central authority stepped in immediately after the event, and the Bubble Act ensured that all future joint-stock companies would require a royal charter, effectively reducing their number.

The Battle of Beachy Head, 1690. The French gain control of the English Channel. How to pay for a new British navy?

© Paul Fearn / Alamy Stock Photo

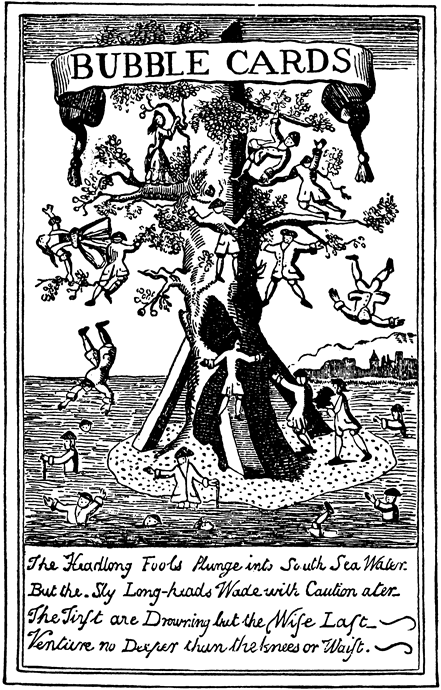

The Headlong Fools Plunge into South Sea Water... Venture no Deeper than the Knees or Waist

Source: Wikipedia

Mississippi Bubble

Britain’s warring neighbour France fared no better. As a result of the Seven Years’ War with England, the royal finances were in a perilous state. Enter Scottish financier, John Law, who in 1716 created the Banque Générale and floated the idea of another joint-stock trading company. The Mississippi Company was granted a trade monopoly of the West Indies and North America by the French government, based on the alleged wealth of the French colony of Louisiana. It took months for news to be relayed from America, so again, people were slow to figure out the truth of what was going on. An effective marketing scheme led to massive speculation in the shares of the company in 1719. And a sustained attack by Law’s opponents attempting to convert their notes into coin en masse, led to the collapse of the Banque the next year.

The secret weapon

Government loans were the essential ingredient to successfully waging war. The French Monarchy opted to fund its debt with short-term annuities and high-interest rates, and this proved to be one of the triggers for the collapse of the country into revolution at the end of the 18th century. Modern central banking was established in France only in its aftermath by Napoleon in 1800. The British on the other hand went for long term or perpetual loans or “Consols” at relatively low rates of interest, which were first issued in 1751. The integration of the bank and state functions was one of Britain’s “secret weapons” in funding its navy, a key underpinning of the expansion of Empire.

Trust and gold

The Bank of England in London features a defensive curtain wall, no ground floor windows or connecting buildings, designed to live up to the saying, “As safe as the Bank of England”

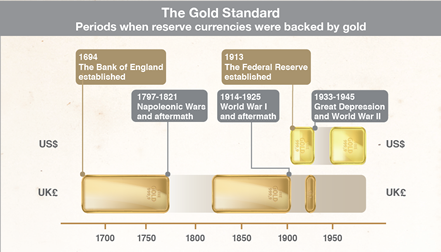

To this day, the Pound Sterling “promises to pay the bearer on demand” the sum represented by the bank note. What this means if you turn up at the Bank of England is difficult to say, but back at the bank’s inception the public was clear: It meant gold. The Bank of England was to have an on-off relationship with its gold standard. Generally, in time of war – and during the great depression of the 20th century – more freedom was required to loosen the money supply, and the bank would go off gold.

The Bank Restriction Act of 1797 was the first get-out clause. Due to an invasion attempt by the French, and a feared run on the pound, the act removed the requirement for the bank to convert banknotes into gold, and the bank only moved back on to what became known as the gold standard in 1821. The Bank Charter Act of 1844, again loosened the relationship with gold. The bank was given a monopoly of the issue of new banknotes backed by £14 million in government debt and thereafter gold bullion. The act served to restrict the supply of new notes reaching circulation, but not the creation of new bank deposits, or loans.

Pound Sterling pegged to the gold standard was to reign supreme until the outbreak of war in August 1914. Then, the Currency and Bank Notes Act gave the bank permission to extend the issue of notes without additional gold reserves. In the 1920s, the United Kingdom struggled to put Sterling back on to gold at the pre-First World War rate of 4.86 dollars to the pound. In 1925, Winston Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer, took the plunge, put the country back on to gold, causing the pound to rise in price, and exports to collapse. The ensuing swift contraction of the economy caused mass unemployment, and a catastrophic General Strike the next year. As the great depression hit causing further unemployment, Bank of England Governor Montague Norman, reluctantly gave up the battle and took Sterling off gold in 1931.

The Federal Reserve

Slowly the practice of central banking was spreading. The newly established German Reich took just five years to establish its Reichsbank in 1876, issuing a very stable currency backed by gold until the First World War. Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the American Civil War, banking remained fragmented in the United States, and endured a series of financial crises. It took Europeans to show the way. Early in 1907, German financier Paul Warburg authored A Plan for a Modified Central Bank in the New York Times Annual Financial Supplement, outlining remedies that he thought might avert panics. A further financial crisis in the same year helped to concentrate minds, and six years later under the new presidency of Woodrow Wilson, The Federal Reserve System was established. This proved timely. During the First World War, the Federal Reserve was to be the issuer of US war bonds.

The United States was relatively late to central banking but was on gold and anchored the international system until the great depression forced a rethink. President Roosevelt took the United States off gold in 1933, prioritising employment as part of his New Deal.

The Gold Standard

Periods when reserve currencies were backed by gold

The German Reichsbanknote of 5th February 1924, 20 billion Marks. The spectre of inflation was to haunt central banks in the 20th century

Source: Wikipedia

Lender of last resort

The Bank of England, privately owned until 1946, was slow to assume broader responsibilities. It had failed to bail out the Overend Gurney wholesale discount bank in 1866, causing a drop in confidence in the City of London. Grudgingly, in response to the promptings of theorists such as Walter Bagehot, the bank accepted a wider role as “lender of last resort” in the 1870s. When Barings Bank came under threat of default in 1890, the Bank of England led a coalition of prominent city institutions who secured a loan to save it. Since then, whether a central monetary authority steps in to bailout a private company has been on a case by case basis. In the 2008 financial crisis, the judgement call in the US went to representative institutions. The initial Senate bill was for a $700 billion bank bailout in October 2008.

The economist as saviour

Several developments in the early 20th century expanded the role of governmental finance. The traditional role of the Treasury in London was manager of the government’s budget. Under the influence of British economist John Maynard Keynes, its role was to be expanded to manager of the economy. The neoclassical economics model held that free markets would, in the short to medium term, automatically provide full employment as long as workers were flexible in their wage demands. But the working class was becoming more organized, as seen in the British General Strike of 1926, and the unemployment problem, which was acute in the early 1930s, could no longer be ignored.

Keynes advocated the use of counter cyclical fiscal and monetary policies to mitigate the adverse effects of economic recession, enshrined in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936. Amongst other proposals he advocated a fiscal response, where the government could create jobs by spending on public works. As he put it, “The economy is socializing itself.”

A barbarous relic

Keynes famously dismissed the constrictions of the gold standard as a barbarous relic, and instead emphasised elasticity of money supply to stimulate the economy. His ambitions went beyond the United Kingdom, which was being economically eclipsed by the United States after the First World War. He envisaged a new set of international agreements to conduct the performance of the international economy, which in the 1930s and 40s effectively meant Anglo-American interests. Somehow, the resources of the United States, the so-called “coming nation”, had to be utilised to assist those of the United Kingdom, the “going nation”. In the Second World War, as Britain faced bankruptcy, the Lend-Lease arrangement guaranteed a free flow of war materials from across the Atlantic.

The Grand Design

In the early 1940s Keynes made a series of proposals for a Grand Design when peacetime arrived. This would involve a clearing union to secure equilibrium in members’ balance of payments, and a machinery of exchange controls. A new international currency, the bancor, would offer an “absolute elasticity” of supply. The proposals culminated in the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement, a fully negotiated monetary order intended to govern monetary relations among independent states, albeit minus the bancor. Bretton Woods gave birth to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The Bretton Woods system of monetary management placed the United States back on gold as the world’s reserve currency at a fixed price of US$35 an ounce. Other major currencies were pegged to the US dollar by fixed exchange rates. In the mid-term these rates proved impossible to hold, and the United Kingdom and France successively devalued their currencies. Finally, weighed down by the stagflation caused in part by the Vietnam war, on 15th August 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended convertibility of the US dollar into gold. Since then central banks have offered nothing but “fiat currencies”.

Brave new distributed world

For the past two centuries, the world’s financial system has been anchored by an increasingly centralized set of authorities, first at national level, and then after the Second World War at international level. From the mid-20th century, economies were managed with increasing ambition and scope as first the American New Deal and then the British welfare state took off. Post-Second World War, the European Coal and Steel Community was to evolve into the European Union, spawning a massive bureaucracy, a European Central Bank, and an ambitious economic, financial and social agenda: Under the EU four freedoms are guaranteed – the free movement of goods, capital, services, and labour. With one or two notable exceptions (Brexit; the US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership), the tendency has been towards ever greater supra-national organizations.

What are the implications for blockchain technology? Over the past decade, distributed ledger technology has begun to offer alternative ways of building trust by consensus. Recent iterations of blockchain can handle contingency, so people can in theory make smart contracts directly with one other. Is blockchain poised to usher in a new era?

Some stumbling blocks: Currently there is fragmentation between public and private blockchains. Moreover, within the various industry sectors, leading corporates are developing proprietary blockchains. Two questions: Is some sort of regulatory authority necessary, particularly to verify digital identities on public blockchains? And, practically speaking, how is interoperability between private blockchains to be achieved? If recent history is any guide to go by, regulatory standards must evolve, and at an international level.

The gold standard is long gone, but the need to protect investors against fool’s gold is as urgent as ever.

Fiat money

“Fiat Money is Representative (or token) Money (i.e. something the intrinsic value of the material substance of which is divorced from its monetary face value) – now generally made of paper except in the case of small denominations – which is created and issued by the State, but is not convertible by law into anything other than itself, and has no fixed value in terms of an objective standard.” John Maynard Keynes in A Treatise on Money, 1930

© Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo