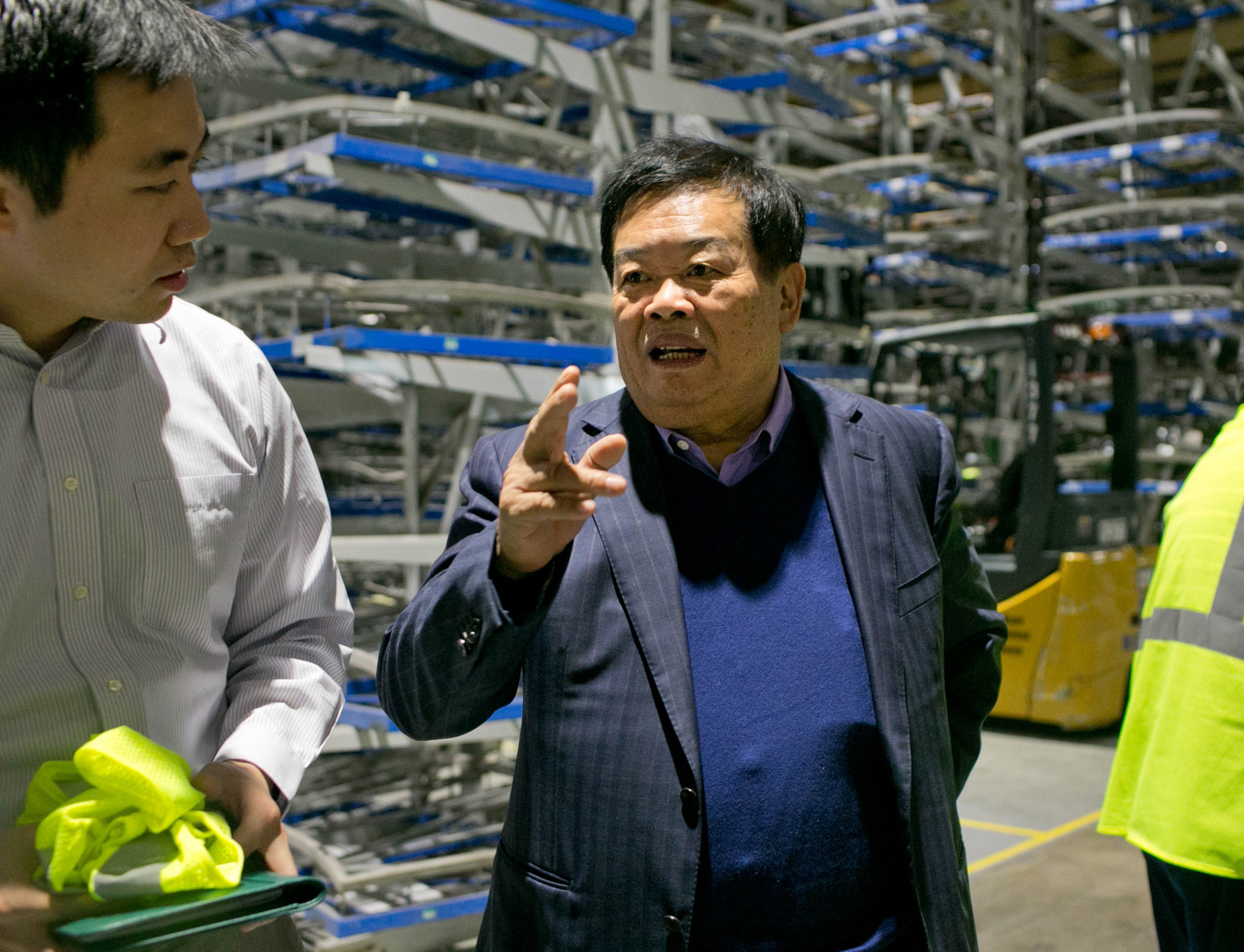

President Trump meets Alibaba boss Jack Ma

President Trump meets Alibaba boss Jack Ma

© Reuters Pictures

Against a background of rising costs, Chinese manufacturing is on the move — to the US and Southeast Asia. Professor Frank Chen, Head and Chair Professor of Management Sciences, investigates latest trends and how a record inflow of Chinese investment is helping revitalize the American economy.

When the then President-elect Donald Trump met Alibaba executive chairman Jack Ma in January 2017, he characteristically said he had a "great meeting". They discussed one of the incoming President's favourite topics, American jobs. The headline news? One million new US jobs to be created.

"We're focused on small business," Ma told reporters after the meeting. "We specifically talked about ... supporting one million small businesses, especially in the Midwest of America."

Ma said that Alibaba's expansion would focus on products like garments, wine and fruits, with a special focus on trade between the American Midwest and Southeast Asia.

Of course, Alibaba has clout. With more than 10 million active sellers as of 2015, the company estimates its China retail marketplaces has contributed to the creation of over 15 million job opportunities.

The meeting came against a background of stalled US reshoring (US companies returning to their homeland) whilst Chinese investment remains buoyant. Every year since 2012, Chinese investment in America has exceeded investment flows in the other direction.1 And in 2016 Chinese companies' investment in the US economy was at a record US$18 billion. This embraced sectors from entertainment to micro-electronics, information technology, household appliances, and hotels. The investment went beyond financial sector mergers and acquisitions to include the building of new manufacturing plant on green or brown field sites.

The world's workshop?

As early as 2010, Bloomberg Business Week ran the title "Why Factories Are Leaving China". Chief Economist at the Industrial Bank, Lu Zhengwei, dates the shift to 2012, when China's services sector overtook manufacturing for the first time as the biggest contributor to nominal gross domestic product. At the time this was heralded as a milestone towards industrial restructuring.

"The process began to get serious a long time ago... When we spoke highly of the increasing role of the service industry in our economic structure, it had already kicked in. That was 2012," Lu said, adding that China's high taxes and high land costs are now turning business away.2

China's manufacturing base is indeed transforming. Lower end manufacturing is moving offshore to Southeast Asia countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia and African countries such as Ethiopia, whilst higher value added manufacturing is encouraged against a background of increasing automation. The heyday of China's manufacturing boom is long gone. These were the 1980s and '90s, and especially the years after China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001. In these years, the gains to China's manufacturing base can often be directly correlated to losses in the US. Some sources state that the US trade deficit with China cost 3.2 million jobs between 2001 and 2013.3Manufacturing was eager to relocate from the advanced economies, and within a decade China was the world's second-largest economy.

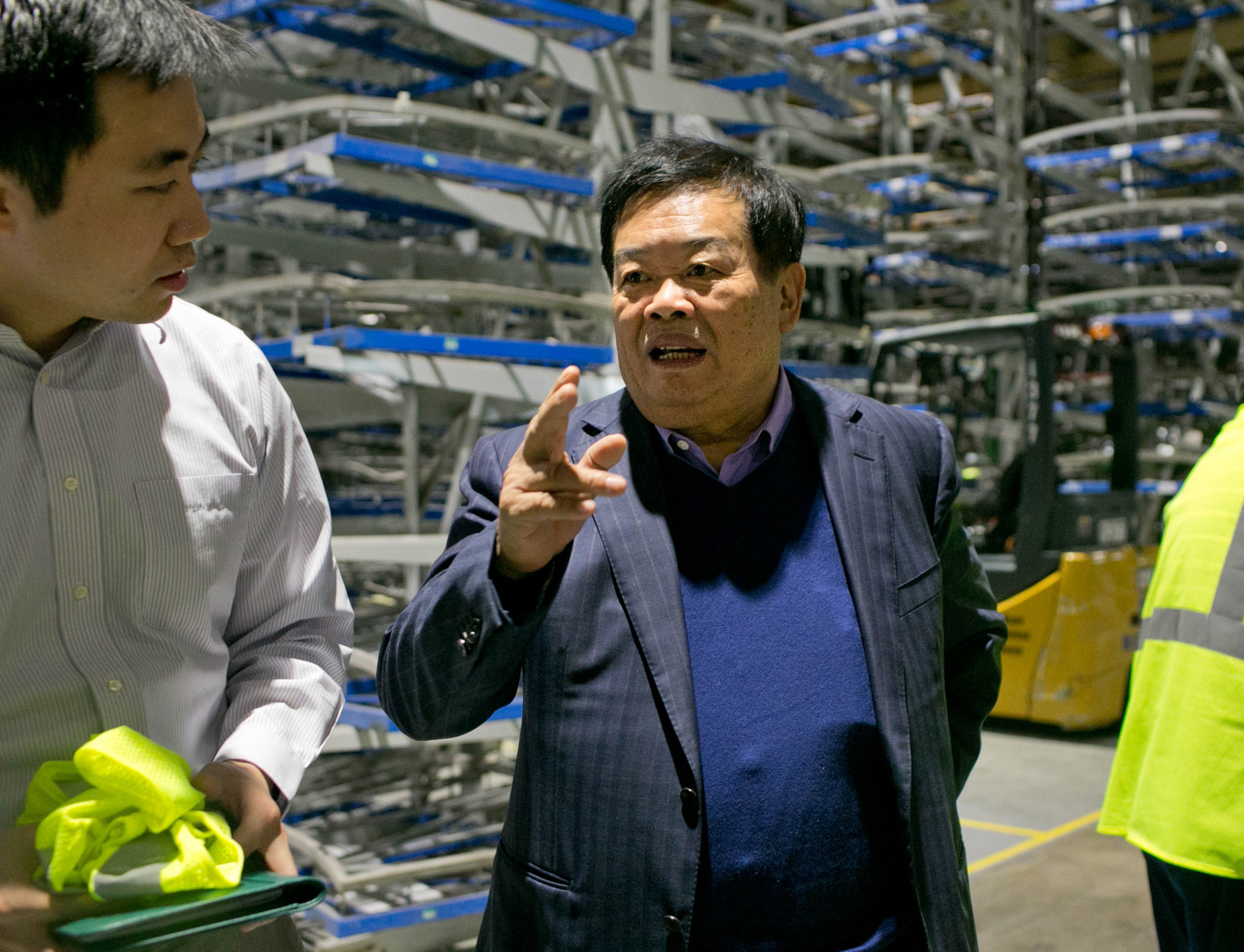

Chairman Dewang Cao tours the Fuyao plant in Ohio

Chairman Dewang Cao tours the Fuyao plant in Ohio

© The Washington Post/Andrew Spear/Getty Image

2016 Record – breaking Chinese investment in the US

- January In the largest China-Hollywood deal to date, conglomerate Dalian Wanda Group Co. acquires production and finance company Legendary Entertainment for US$3.5 billion.

- April Omnivision Technologies, whose camera sensors have been used in Apple Inc.'s iPhone, is acquired by a consortium of Chinese private equity firms including CITIC Capital Holdings, Hua Capital Management and Goldstone Investment Co. for US$1.9 billion.

- April Tianjin Tianhai buys Ingram Micro for US$6.07 billion. The deal marks the largest Chinese takeover of a US information technology company to date.

- June Qingdao Haier Co. spends US$5.6 billion to buy the appliance division of General Electric, giving the Chinese appliance manufacturer an opportunity to boost its presence in the US market.

- September Anbang Insurance's, one of China's largest insurance companies, completes a US$6.5 billion deal for Strategic Hotels and Resorts.

- October Chinese conglomerate HNA agrees to pay private equity firm Blackstone Group US$6.49 billion for a 25% stake in Hilton. The move is part of HNA's efforts to enhance its global tourism business.

Southeast Asia boom

A confluence of political and economic factors is now producing another decisive shift – away from China. On both sides of the Pacific, government policy is playing a role. In China, Beijing has encouraged labour-intensive businesses to move elsewhere as it tries to steer the economy towards higher value-added services and automation. In the US, President Trump has suggested that a tariff barrier may be placed between the two countries, and encourages "Made in America". The question remains, who by?

Automated car manufacture at the Beijing Hyundai Motor Company

Automated car manufacture at the Beijing Hyundai Motor Company

© Tomohiro Ohsumi/Bloomberg via Getty Images

For China, the new policy means less emphasis on shoes and apparel. Vietnam has overtaken China to become the largest producer for Nike shoes. Garment exports from Southeast Asian nations to the EU, US, and Japan have been very strong in recent years, sharply contrasting with the performance from China. Companies such as Eclat Textile, Taiwan's largest apparel company, are pulling out of China completely due to deteriorating business conditions and surging wage costs.

Even the high-tech sector is affected. More than 50% of Samsung smartphones are now assembled in Vietnam, and one more Samsung factory is currently under construction. It is reported that 80% of Samsung's China capacity will be moved to Vietnam. When such giants move, so do their immediate supply chain partners, sooner or later, followed by secondtier and accessory suppliers. The result – many Vietnamese companies are also intensifying investment in the electronics supporting industry.

Exodus

The exodus of Chinese manufacturing goes hand-in-hand with a surge of outbound investment. This is up more than 50% in the first 11 months of 2016 from a year earlier, with manufacturers involved in more than a third of China's overseas mergers during that period. At the same time, China's private sector investment at home rose just 3.1%.

The prospect of reaching a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement accelerated such supply chain shifts. TPP would make Vietnam an open economy and a favourable destination for FDI. With other ASEAN countries intent on joining too, a pattern similar to 1990s' Pearl River Delta was emerging with countries such as Indonesia introducing economic stimulus packages to encourage foreign investment, and keeping currency at low levels. The whole regional block was poised to replace the Pearl River Delta region, benefit from lower labour costs, and emerge as the world's low cost manufacturing centre.

President Trump's abrupt cancellation of TPP has now thrown doubt on the viability of importing to the US. In the short-term, reshoring and FDI in the US should gain renewed impetus. But one thing is for sure, these manufacturers will not be returning to China.

FDI trumps reshoring

Ironically, Foreign Direct Investment seems to be playing a much greater role in the American manufacturing revival than the much-vaunted US reshoring phenomenon.

"The US Reshoring phenomenon, once viewed by many as the leading edge of a decisive shift in global manufacturing, may actually have been just a one-off aberration," says Patrick Van den Bossche, A.T. Kearney partner and co-author of an April 2016 Reshoring Index study. Industries vulnerable to rising labour costs in China have been successfully relocating to other Asian countries, rather than returning to the US, the report confirms. Vietnam has absorbed the lion's share of China's manufacturing outflow, especially in apparel. US imports of manufactured goods from Vietnam in 2015 were nearly triple the level of imports in 2010.

'Made by China' in America

China companies are entering manufacturing in the US in a variety of industries.

- Paper In June 2014 Shandong Tranlin announced it would invest about US$2 billion to build a pulp and paper factory outside Richmond, Virginia.

- Textiles The Keer Group has built a US$218 million cotton yarn factory in South Carolina, and "are now hiring in places where cotton was king".

- Construction Machinery SANY has made a US$60 million investment in office and manufacturing space for construction machinery in Georgia.

- Computers Lenovo opened a computer production plant in North Carolina in June 2013.

- Auto Parts China's largest auto parts maker, Wanxiang Group, has 28 factories in 14 US states with 6,500 employees.

- Garments In October 2016, Chinese garment manufacturer Tianyuan Garments Co. made a US$20 million investment to produce clothes for brands like Adidas, Reebok and Armani – the first Chinese manufacturer to make clothing in the US.

- Paper In April 2016, Chinese paper products maker Sun Paper Industry said it was opening its first North America factory in South Arkansas, investing more than US$1 billion to construct a new bio-products mill that would create 250 local jobs.

- Steel Pipe Tianjin Pipe has invested more than US$1 billion in a steel pipe plant in Texas, designed to produce 500,000 metric tons per year of steel pipe that is used in the oil and gas industry.

Just a day away

Over in America, Chinese investment is creating much sought-after manufacturing jobs. After nearly 60 years of manufacturing in China, Tianyuan Garments Co is the first Chinese garment manufacturer to set up shop in Arkansas. Cutting distance to customer is a major motivator.

"We're midway between Canada and Mexico and a one-day's truck drive to 60% of the US population," says Mike Preston, Executive Director of the Arkansas Economic Development Commission.

Tianyuan still operates five factories in China, but it sees its biggest market opportunity as North America. Arkansas' ecosystem as a cotton producing state is especially attractive to textile and clothing manufacturers. And incentives are on offer. In return for its investment, Tianyuan receives a US$1 million infrastructure grant, US$500,000 for training assistance and a 3.9% annual tax rebate, which comes to about US$1.6 million annually. It's a win-win situation as Tianyuan expects to hire 400 American workers to run the refurbished factory, due to open in late 2017.4

Another prominent mover is China's largest auto glass manufacturer, Fuyao Glass. According to founder and chairman, Dewang Cao, in the US "land is basically free, the price of electricity is half of that in China, and the natural gas price is only one-fifth." Fuyao Glass plans to open a third American plant this year, bringing its total investment in the US to US$1 billion.2

Robo-boom

Manufacturing is in fact booming in the United States and in 2016 hit an all-time record. Strangely, this achievement is not much touted. And the reason is that it is down to automation. The US makes 85% more goods now than in 1987, but with only two-thirds the number of workers, an inconvenient truth in a time of populist politics promising the return of jobs to America.3

The next question is, who makes the robots? According to the International Federation of Robotics, in 2013 China became the world's largest market for industrial robots.4 In 2014, President Xi Jingping called for a robot revolution, and by the end of 2016 China was scheduled to overtake Japan and become the world's biggest operator of industrial robots.7 China is now working to extend the use of robots beyond factories, to agriculture and a range of other applications. As labour costs rise, and spurred on by government support, robots are on the march, especially in the rich coastal provinces where Guangdong alone is set to invest US$8 billion on automation between 2015 and 2017. The result? Higher productivity with fewer workers.

Goodbye to Made in China?

No one expects manufacturing to disappear from the rich coastal areas of China. The complex networks of suppliers for industries from textiles to electronics would take years to build up elsewhere.

But findings from the Trends in Global Sourcing Survey, a survey of global procurement and purchasing executives which assesses the risk environment and sourcing trends, indicate that support for China as a low-cost sourcing destination is waning.

"The share of respondents who agree that China is a low-cost sourcing destination dipped below 50% for the first time in 2016," said Paul Robinson, economist at IHS Markit. "This was down markedly from 70% in the 2012 survey."8

China is increasingly viewed as a hub of global supply chains. But for some companies in areas such as chemicals, plastic and yarn that are heavy on energy and light on labour, moving to the US can save costs. And President Trump's much-touted corporation tax cuts would only increase incentives.

Many Chinese companies plan to keep more high-end work in coastal China while moving less sophisticated work elsewhere. The One Belt One Road infrastructure expansion westward sets the seal on the move into relatively new territories. Central Asia beckons.

Brand America

For one iconic US manufacturer, Donald Trump's win in November was the final nudge to move production back home from China. Trans-Lux makes the digital screens at the New York Stock Exchange. The company has a rich manufacturing legacy, was the pioneer of electronic ticker technology, and installed its system at the NYSE back in 1923. But for the past two decades those screens have been made across the border from Hong Kong in Shenzhen. Now, shifting production back to the US could have advantages beyond reducing costs.

"Compared to 1997, labour costs are much higher, shipping costs are monstrous and it's very hard to find a new facility to expand our production," said J.M. Allain, President & CEO of Trans-Lux.

"It makes economic sense," he said. But more than that: "At the end of the day, there's also cachet attached to a made in America brand."9

As Chinese manufacturing companies migrate across the Pacific, he is clearly not alone in wanting to reinvigorate Brand America.

Distribution by truck in the US

Distribution by truck in the US

© Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP/Getty Images

- ^Wee, H. (Feb 6, 2015). The rise of ‘Made by China' in America. CNBC. Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2015/02/05/the-rise-of-made-by-china-in-america.html

- ^Leung, S. (December 30, 2016). Is the world's factory ‘hollowing out' as manufacturers pack up and leave China?. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/2058175/chinese-manufacturing-hollowing-out

- ^Kimball, W. & Scott, R. E. (December 11, 2014). China Trade, Outsourcing and Jobs. EPI Briefing Paper #385.

- ^Kavilanz, P. (December 30, 2016). Chinese manufacturers are setting up shops in the US. CNN. Retrieved fromhttp://money.cnn.com/2016/11/30/technology/chinese-manufacturers-come-to-america/index.html?iid=ob_homepage_tech_pool

- ^Woodall, B. (October 7, 2016). Fuyao Glass investing $1billion in US factories: chairman. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-fyg-usa-idUSKCN1262M0

- ^Manjoo F. (January 25, 2017). How to Make America's Robots Great Again. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/25/technology/personaltech/how-to-make-americas-robots-great-again.html?_r=1

- ^Bland B. (June 6, 2016). China's robot revolution. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/1dbd8c60-0cc6-11e6-ad80-67655613c2d6

- ^HIS Markit (January 30, 2017). China's Role in Supply Chains Continues to Grow, Moves Beyond that of a Low-cost Provider. Retrieved from http://news.ihsmarkit.com/press-release/commodities-pricing-cost-media/chinas-role-supply-chains-continues-grow-moves-beyond-l

- ^Kavilanz, P. (December 7, 2016). Trump's win pushed this manufacturer to return to the US. CNN. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2016/12/07/technology/translux-manufacturing-trump/